The Surprising History of the Vibrator

Bullet, rabbit, wearable, G-spot, suction. Since its debut back in the late 1800s, the vibrator and its many forms have remained a staple for personal ecstasy. In that time, it has evolved and morphed into a versatile toy that can be used for a wide variety of genital stimulation. With the passage of time, sex and pleasure have become more openly celebrated, and so has the vibrator.

Let's start around 69 to 30 B.C.

Cleopatra, a ruler of ancient Egypt, has often been credited with inventing the first primitive vibrator: a little box or dried gourd filled with bees. As inventive as this sounds, there's no archeological evidence for the story and British scholar Helen King denounced its validity. Yet the myth persists, perhaps because the idea of Cleopatra's DIY bee vibrator validates the fierceness of female sexuality and the importance of pleasure throughout time.

The truth of the first electric vibrator, the bullet's and rabbit's ancestor, is a little less remarkable than a box full of bees. The percussor, colloquially known as Granville's hammer, was invented in the early 1880s by physician Joseph Mortimer Granville as a way of stimulating and calming the nervous system.

The invention was advertised to other physicians as a medical tool and, eventually, to anyone with electricity as a useful household item. Once other companies began creating their own versions of vibrators, advertisements began proclaiming it as a cure for nearly anything, from muscle aches to diarrhea. Granville proposed their use for men exclusively, and it's argued this was because he was in some way aware of the potential use for female masturbation.

In Granville's book on the benefits of his vibrator, he wrote: "I have never yet percussed a female patient...I have avoided, and shall continue to avoid the treatment of women by percussion, simply because I do not wish to be hoodwinked, and help to mislead others, by the vagaries of the hysterical state."

Hysteria and the vibrator

At the time of the vibrator's invention, hysteria was a common diagnosis for women. Its symptoms included anxiety, aggression, irritability, fainting and nymphomania, to list a few. Though a very general diagnosis, hysteria became synonymous with female sexuality.

"Thanks to our popular culture and its fascination with fake history, when we hear the word 'hysteria,' we automatically think it has sexual connotations," said Fern Riddell, a British historian and author who specializes in sex and Victorian culture. "However, in the past, it was simply the term used for female ailments and disorders, especially if they were to do with mental health or the nervous system.

"It wasn't until [psychoanalyst] Sigmund Freud, at the very end of the 19th century, that the popular connection between sex and hysteria was made, but that's because, to Freud, everything was about sex," she explained. "It's really a 20th- and 21st-century issue that redefined hysteria as being sexual."

Freud theorized that symptoms of hysteria manifested through repressed memories of sexual abuse or, in some cases, through fantasies of such abuse. Freud's theory was the seed of the mass misunderstanding of hysteria, and the crux of one of the more famous vibrator myths: that they were used by doctors to "cure" hysteria.

Continued hysteria misinformation

One of the first books of vibrator research, "The Technology of Orgasm," written by Rachel Maines and published in 1999, proposed the theory that medical masturbation achieved "hysterical paroxysm"—the 17th-century term for orgasm—as a cure for hysteria.

A number of historians, such as Hallie Lieberman, take issue with Maines' book. Lieberman disputed Maines' claim that Victorian-era doctors had little to no understanding of the female orgasm. Lieberman pointed to several studies proving an understanding of female sexuality at that time. She also checked several of Maines' sources citing gynecological massage as a cure for hysteria and found most weren't directly related, making the connections a stretch.

In response to these objections, Maines held tight to her claim being a hypothesis. In an interview with Big Think, she said: "People just loved my hypothesis, and that's all it is really, is a hypothesis, that women were treated with massage for this disease, hysteria…and that the vibrator was invented to treat this disease. Well, people just thought this was such a cool idea that people believe it, that it's like a fact. And I'm like, 'It's a hypothesis! It's a hypothesis!'"

In 1980, hysteria was removed from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. But thanks to our collective love of sex, a number of media outlets fell in love with theories like those of Freud and Maines, cementing the false notion that hysteria was a sexual disease formally thought to be cured by vibrators.

How did the vibrator change from a medical toy to a sex toy?

As doctors began to speak out against the vibrator's value in the medical field, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) started cracking down on the sales of patented medical aids. This forced companies that were producing vibrators to reevaluate how they represented their uses. They could no longer suggest vibrators help you lose weight or cure your nausea—vibrators had to find a new purpose.

The first big step toward today's perception of the vibrator came in 1903 when a "sexual vibrator for men and women" was advertised, according to both Maines' book and Lieberman's article "Selling Sex Toys."

"It kind of looked like this belt with electricity and vibration," Lieberman explained, a far cry from the vibrator we know and love today. Lieberman's article explores the early strategic marketing that allowed the vibrator to reach its ultimate form and purpose. From 1903 until the '60s, vibrators were vaguely advertised as helpful household massagers, with subliminal suggestions for sexual use, particularly for women.

Lieberman explained the language of ads was never fully erotic due to anti-obscenity laws, but subtle phrases conveyed messages that spoke to people interested enough to purchase a vibrator for its clandestine suggested use.

The evolution of sexual openness in the 1950s

Alfred Kinsey's 1953 research on female sexuality indicated 62 percent of participants masturbated. This statistic may feel normal, if not underwhelming, to us today, but at the time this kind of information had yet to be outwardly addressed and statistically proved.

In the 1960s, there was an explosive sex-positivity movement, led by artists and sex educators such as Betty Dodson, the woman who famously created and led the first masturbation workshop for women. In these two-hour sessions, women were guided to connect with their bodies through masturbation with wand-shaped vibrators. Dodson taught thousands of women her masturbation method, catapulting vibrators into the mainstream and solidifying them as a key tool in solo sexual satisfaction.

In the 1980s, vibrators begin to sell

Some of the first sex toy manufacturers hit their stride in the 1980s when they began experimenting beyond the classic wand-style vibrators. For heightened stimulation, vibrators accompanied by dildos—now famously known as "rabbit-style" vibrators—began popping up on the market, and by the late 1990s became one of the most popular sex toys available.

During the time of their conception, vibrators conjoined with a dildo had a hard time concealing their sexual use in countries with strict obscenity laws. In order to get around laws in the countries where they were being produced, manufacturers began marketing vibrators with bright colors and animal shapes. As we now know, the name "rabbit" was the one to stand the test of time.

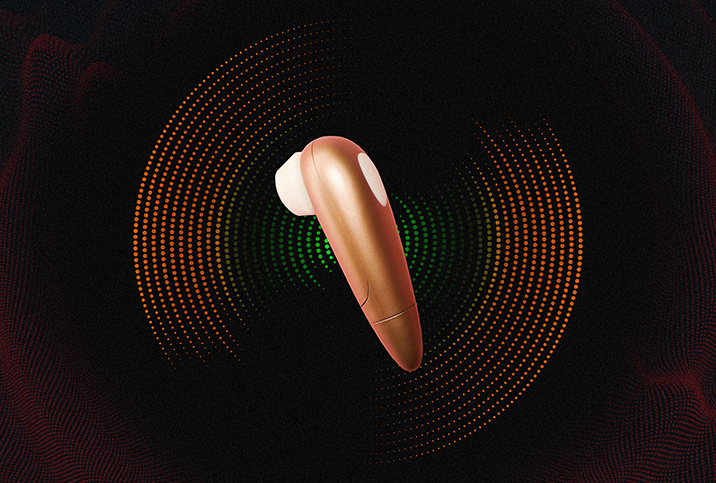

We can track the vibrator's physical evolution and its growth in popularity from the 1960s to the 1990s, and it's all directly correlated to the public's perception of sex. In 2021, the sex toy industry in the United States generated more than $12 billion and accounted for a 33 percent stake in the global market. Today, more than 10 different styles of vibrators are on the market.