The Grim Origin of Syphilis

Syphilis went by many names, such as "Black Lion," "The Great Pox" and "The Great Imitator." For centuries, the virus spread, sparing no one, not even kings, philosophers, popes, artists, writers and, of course, the commoners.

The origin of syphilis included symptoms that were horrific, ravaging the bodies of victims for decades before death. Sufferers were often shamed and ostracized from society, visibly disfigured and eventually turning mad throughout the disease's final stages.

Syphilis is on the rise again, but because of penicillin, most modern sufferers won't face the dramatic effects our ancestors did. Now, the sexually transmitted disease (STD) can be cured with antibiotics, but the history of syphilis dates all the way back to Columbus' return to Spain, when its grim reign of terror ravaged society.

What is syphilis?

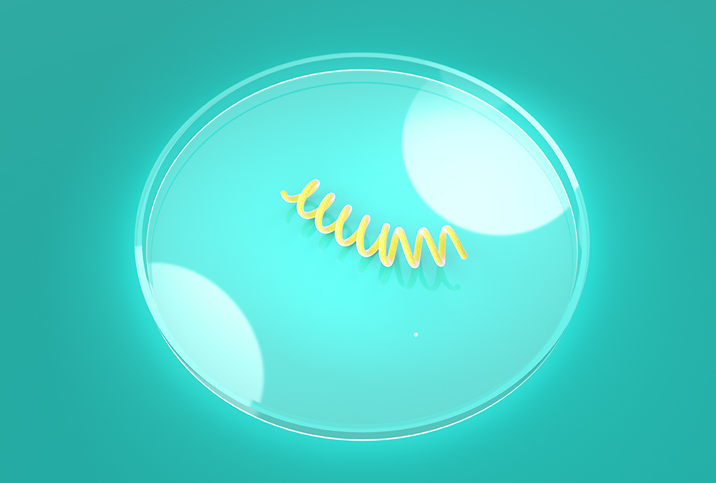

Syphilis is a bacterial infection typically transmitted through sex, though it can be passed to a child during pregnancy, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The corkscrew-shaped bacteria responsible for venereal syphilis, Treponema pallidum, is one of four related subspecies of the Treponema family, which is also responsible for bejel and yaws.

Don't Google syphilis's stomach-churning symptoms during lunch—they are far too vast in number. Syphilis was called "The Great Imitator" by Canadian physician Sir William Osler because it presented such a diverse array of symptoms, particularly in its later stages, simulating almost every disease known to man.

Untreated syphilis progresses through four stages, according to the CDC. During the primary stage, the infected person may notice one or more sores on their body. Typically, these sores are painless and go away on their own in three to six weeks.

This doesn't mean the infection itself has vanished, however. During the secondary stage, skin rashes and/or lesions around the mouth, genitals or anus can appear, possibly accompanied by headaches, weight loss, fatigue and muscle aches.

Like the initial sores, the secondary stage symptoms disappear on their own. The disease then enters a latent stage, where the infected person may not experience symptoms for many years.

Approximately 10 to 30 years after infection, the disease erupts into the tertiary stage. During this destructive phase, the disease wreaks irreparable damage to bones, internal organs, the nervous system, skin and the cardiovascular system, and tumor-like inflations all over the body called "gummas" are also common.

Neurosyphilis—when the disease spreads to the nervous system—can occur in the fourth stage, too. As the disease spreads to the brain and spinal cord, it can cause dementia, blindness, personality changes, delusions, seizures, depression and paralysis.

Syphilis's origins

The exact origin of syphilis is subject to debate. Historical records may be muddied by cultural prejudices and archaic medicine, while paleopathological studies struggle to distinguish venereal syphilis from other Treponema diseases, such as yaws, a skin infection that also causes skin and bone lesions.

One of the more prominent theories is the "Columbian hypothesis," suggesting explorer Christopher Columbus and his crew brought the disease from the New World to the Old, according to a history published in the Journal of Medicine and Life. Other theories argue that the disease either existed in the Old World long before Columbus or emerged from other Treponema strains wherever geographic, climatic and cultural conditions allowed.

Regardless of its inception, the earliest European accounts of a syphilis outbreak happened shortly after Columbus returned home from sailing the ocean blue. In the battle of Fornovo in July 1495, Italian doctors reported a ghastly new disease ravaging the bodies of some of the invading French soldiers. The disease spread through sexual contact and often led to death.

However bleak the prognosis of untreated syphilis is today, early accounts suggest it used to be much worse. The syphilis of old was more virulent, spreading faster and killing victims much more quickly, possibly due to the unprepared European immune system.

Syphilis rapidly spread to the rest of Europe, then throughout the Old World. In August 1495, Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian I warned of a heretofore unprecedented disease that was a punishment from God for blasphemy. By Good Friday in 1508, churchgoers avoided the traditional practice of kissing Pope Julius II's feet, which were covered in syphilitic sores.

The myth of syphilis

Initially, Europeans referred to syphilis as "pox" and often "The Great Pox" to distinguish it from smallpox. The term "syphilis" itself came from 16th-century Veronese poet Girolamo Fracastoro, who wrote a Greek mythos fanfic of the disease's origins.

In Fracastoro's epic poem, "Syphilus" was a shepherd who refused to worship the sun. In revenge, Apollo makes him patient zero of his namesake disease, which he soon spreads to his neighbors.

"From him the malady received its name/ The neighbouring shepherds catch'd the spreading Flame," Fracastoro wrote.

Of course, there was even less certainty about the nonmythical origin of syphilis back then. No country wanted to take responsibility for this foul and shameful disease, sparking a worldwide game of finger-pointing.

Everywhere syphilis was found, people blamed their enemies and, more often than not, named the new disease after them. According to a 2005 journal article titled, "History of Syphilis," by Bruce M. Rothschild: "[The] Germans and English called it 'the French pox'; Russians, 'the Polish sickness'; Poles, 'the German sickness'; French, 'the Neapolitan sickness'; Flemish, Dutch, Portuguese and North Africans, 'the Spanish sickness' or 'the Castilian sickness'; and the Japanese, 'the Canton rash' or 'the Chinese ulcer.'"

Marie McAllister, an English professor at the University of Mary Washington who studies medicine in literature, said wild speculation on the disease's origins continued for several centuries.

In the 16th century, the "pox" was commonly linked with New World exploration, she wrote in an email, though some people argued it was caused by cannibalism or represented divine punishment.

Women were blamed in the 17th and 18th centuries, not just as potential spreaders of the disease but as the cause of it. Some writers believed promiscuous women could spontaneously generate the disease in their body, McAllister said. Marginalized groups such as Indigenous people, Jews and the ever-guilty ambiguous foreigners were also popular targets.

"Over time, women, ethnic minorities and 'foreigners' seem to come in for the most blame, but there [was] plenty of blame left for promiscuous men of every sexual preference," McAllister said.

Syphilis treatments

Several centuries passed before effective treatment for syphilis was discovered. Before the 1900s, treatments ranged from wholly ineffectual to occasionally fatal.

Mercury was one of the more common treatments for syphilitic Europeans, hence, the common saying depicted in an engraving by Jacques Laniet: "Pour un plaisir, mil douleur," or "For a night with Venus, a life with Mercury."

Doctors used suffumigation, injections and oral and topical administrations of the toxic metal on patients. Mercury poisoning deaths were a common result, according to a history published in the Journal of Military and Veterans' Health.

Others believed guaiacum, a botanical brought back from the New World, could cure syphilis. The plant caused diarrhea, excessive sweating and urination, and many physicians incorrectly believed the purgative effects expelled the disease from the body.

The first modern breakthrough in syphilis treatment was the development of Salvarsan—an arsenic-derived drug—in 1910. Salvarsan was the first genuinely effective treatment of syphilis, winning its creator, German scientist Paul Ehrlich, a Nobel Prize.

Though Salvarsan actually worked, effective administration of arsenic to treat syphilis proved complex and the drug produced toxic side effects in patients. It wasn't until 1943, when penicillin was introduced, that syphilis could be cured without the threat of severe liver damage.

The Tuskegee study

Once penicillin offered an inexpensive, safe and effective manner of treating syphilis, there was no longer any reason that anyone who sought treatment for the contagious and deadly disease should be denied it.

But in the United States, a study was already underway that purposefully did just that. In Macon County, Alabama, the U.S. Public Health Service conducted the Tuskegee Study of Untreated Syphilis in the Negro Male, a 40-year experiment that began in 1932.

The Tuskegee experiment's expressed goal was to "observe the natural history of untreated syphilis" in Black men, according to an account by Ada McVean, of McGill University. Participants were told they would receive treatment for "bad blood," a colloquial term for an array of afflictions, including syphilis.

In reality, Tuskegee researchers took extensive steps to prevent their subjects from receiving any treatment in order to better understand the natural progression of the disease. They provided participants with syphilis with ineffective medicine (including small doses of mercury) and warned local doctors against treating them.

It wasn't until 1972—long after antibiotic cures had been discovered—that public outcry led to the experiment getting shut down. By that time, many of the study's 399 subjects with untreated syphilis had either died and/or spread it to family members.

"By this time, only 74 of the test subjects were still alive," McVean wrote. "[One hundred twenty-eight] patients had died of syphilis or its complications, 40 of their wives had been infected and 19 of their children had acquired congenital syphilis."

Syphilis today

Since hitting a historic low in 2000, syphilis cases are once again surging. In 2019, the CDC reported a 70 percent increase since 2015, with more than 130,000 reported cases in the United States.

Due to modern antibiotic treatments, syphilis is no longer the terrifying specter it once was, and death rates are much lower. One exception is congenital syphilis—transmitted from mother to unborn child—which still presents a serious threat to infants.

The war against the Great Pox may be all but over, but the history of syphilis still casts its shadow in the era of COVID-19. Many Black Americans pointed to the Tuskegee experiment as a source of their initial vaccine hesitancy, according to the New York Times, expressing deep distrust of federal healthcare.

Meanwhile, echoes of the stigmatization, fear-mongering and blame that accompanied syphilis can be found in our latest pandemic, McAllister said.

"As Susan Sontag writes, humans have always managed to see epidemics as invasions from outside and to associate them with the marginalized," McAllister said. "Such a perception lets us distance ourselves in a time of fear...But ending a pandemic means recognizing that we cannot control everything, then working together to do everything we can."