Flesh, Metal and Fire: A Review of 'Titane'

It began with a nightmare. After the unexpected, whirlwind success of her debut film, "Raw," French director Julia Ducournau was anxious about her next move. After all, where does one go after whipping the film world into a frenzy with a movie about a vegetarian vet-turned-cannibal? Then, one night, she dreamt she was giving birth to car engine parts. And so was born the infamous, transgressive, stunning 2021 Cannes Palme D'Or winner, "Titane."

A lot has been made about the sensationalism of the film—the BBC went as far as to call it, "The most shocking film of 2021." In many ways, it is. Set to a backdrop of hammering music and the garish, colored lights of a seedy nightclub, "Titane" is a wild, nightmarish ride that sends us, clashing and clanking, through a relentless terrain of desire, sex, violence and body horror.

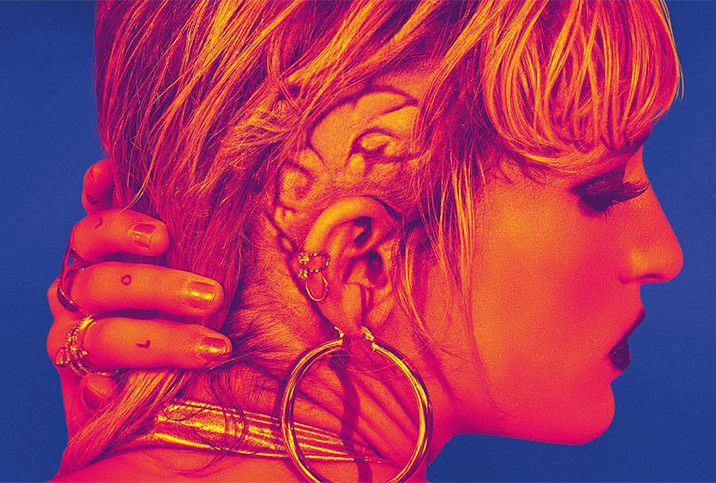

There is a sex scene between a woman and a car; a stomach-churning self-inflicted nose break against a sink; and a murder by way of a metal pin jammed into an ear. Suffice to say, "Titane" is not for the faint of heart. And yet, for all of its lurid grotesquery, it offers moments of piercing humor and a dark, otherworldly beauty.

We open with a young girl and her father in a car. She is a creepy, bad seed sort of child, humming to the revving engine, staring unblinkingly at her unsettled, disinterested father in the front seat. Suddenly, she unbuckles her seatbelt. Her father spins around, loses control of the vehicle, smashes into a barrier and sends her flying.

The young Alexia survives, thanks to the insertion of a metal plate just above her right ear. Titane, French for the metal titanium, is now a part of her.

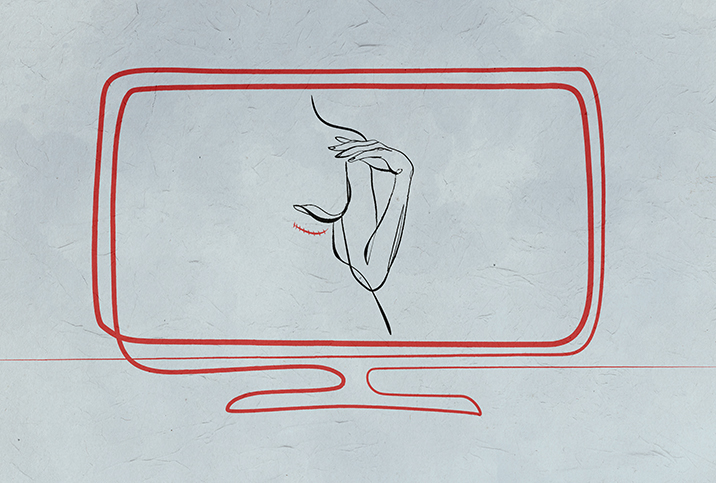

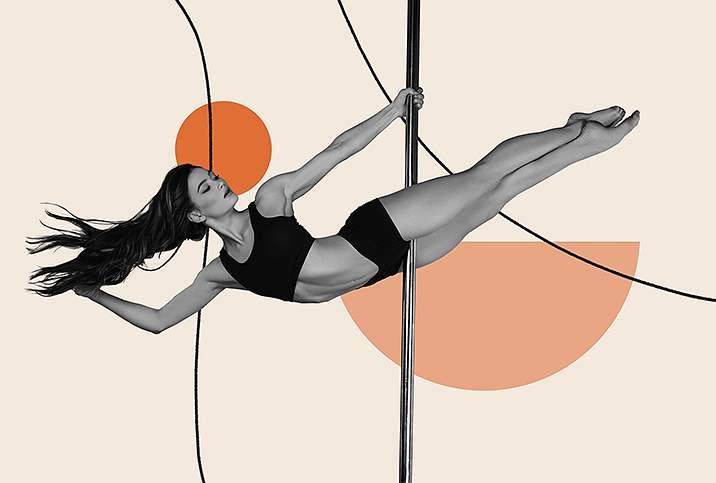

As an adult, Alexia (Agathe Rousselle) is a fierce loner. She's an erotic dancer who performs on cars for a troop of devoted, drooling male fans. And she's also, it turns out, a serial killer: When a fan follows her to her car after the show, she removes a long metal pin from her hair and slams it into his skull. Shortly after the kill, she returns to the dance floor, clambers into the back seat of the car from her performance, and—well—gets it on with said car. In "Titane," violence and sex are never far apart.

Alexia's idyllic dancing, killing, car-loving life goes up in flames when her stomach suddenly begins to grow at a rapid rate. When she starts leaking black motor oil, we can only assume the car has impregnated her. Then, one of her victims gets away. She burns down her home, along with her parents locked inside, and goes on the run. To avoid being caught, she transforms—by way of haircut, eyebrow shave, nose break and body binding—into Adrien, a 17-year-old boy who has been missing for years. His father, a steroid-taking firefighter captain called Vincent (Vincent London), accepts her as his son with open arms.

Within this probing exploration of gender fluidity and the perception of gender are three elements that crash into one other—sexually, violently, intimately. Flesh, metal and fire.

Cross-dressing is an age-old literary trope. It pops up in the Greek myth of Achilles, in Shakespearean heroines like Portia, Rosalind and Viola, and in Virginia Woolf's "Orlando." But Alexia's transformation into Adrien is a little less straightforward.

For one thing, this portrayal of cross-dressing is excruciatingly violent, filled with close-up shots of Alexia's body as she wrestles the binds around her breasts and ballooning stomach. The physical pain is palpable. In fact, we begin to dread the moments of transformation as much as we do the graphic moments of body horror.

Ducournau plays with the dichotomy of gender and, ultimately, does away with it altogether. Instead, she offers a more fluid alternative. Neither man nor woman seems to encapsulate Alexia-Adrien, and no scene better showcases this fluidity than when she goes from headbanging in a mosh pit of partying firemen to repeating her sultry, erotic dance moves atop a firetruck in the guise of Adrien. Like much of the film, the moment is both unsettling and hypnotically beautiful.

Meanwhile, a bond forms between Alexia-Adrien and Vincent, which veers more and more toward sexual desire. It's an uncomfortable pairing, with strong incestual undertones. At one point, Alexia, dressed as Adrien but without her binding, puts on a long yellow dress. She has Adrien's face and bald head with a pregnant woman's body. She is, at that moment, both entirely woman and man. Vincent sees her and shows her a picture of Adrien as a boy wearing the very same dress. "No one can tell me you aren't my son," he says, though it has become clear she is not.

Within this probing exploration of gender fluidity and the perception of gender are three elements that crash into one other—sexually, violently, intimately. Flesh, metal and fire. The camera pans across the battered, tattooed body of Alexia and the muscular frame of Vincent, while metal and fire sear, scar, break, tear and burn their bodies.

As the metallic fetus grows inside her, Alexia's flesh incrementally refuses to cooperate. She scratches and tears at the skin on her stomach, her wraps leave purple and red gashes and bruises across her body, her breasts leak black tar. Ultimately, her metal-infested body bursts free, leaving her naked, deformed and monstrous.

Ducournau, who has said that her metallic creature was inspired by Mary Shelley's "Frankenstein," finds her own vision of humanity within her monster. Of course, the idea of "the monster" ties back to the notion of gender fluidity. Monsters in literature are often seen as symbols of queerness—they represent the other, the unnatural and the societally shunned.

When we dig a little deeper, when we get to know the monster, we begin to understand their perspective. Their violence, their desires, even the unhuman materials they're made of begin to make a little more sense. "I've always thought it was very beautiful the way that the monster is humanized through violence," Ducournau told Slant. "The more violent it becomes, the more it actually becomes human."

If you are looking for meaning in "Titane," it lies here. In the metallic monstrosity of Alexia, we can perhaps discover the beauty in the monsters we hide within ourselves.