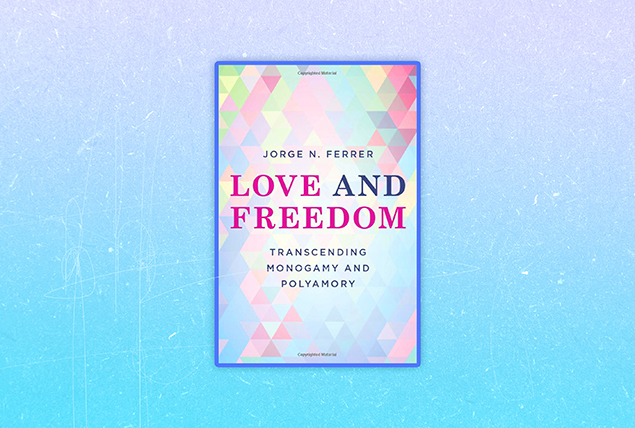

Between the Pages: 'Love and Freedom: Transcending Monogamy and Polyamory'

Jorge N. Ferrer, Ph.D., suggests a shift in how we think about romantic relationships in "Love and Freedom: Transcending Monogamy and Polyamory." In the book (out now on Rowman & Littlefield) Ferrer explains how the overcoming of the relational style binary opens fresh possibilities for thinking about love and sexuality.

"Love and Freedom" proposes the idea of "relational freedom," meaning you can choose your relational style increasingly free from biological, psychological and social conditionings.

You can watch Ferrer on YouTube for his recent TEDx Talk in a personal and highly engaging discussion about his book.

Ferrer is a clinical psychologist and relationship counselor. He served as professor and department chair at the California Institute of Integral Studies, San Francisco. His work has been featured in podcasts and journals, including "Sexuality and Culture" and "Psychology and Sexuality."

Editor's Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell us about your background in psychology and counseling and how it led you to write the book.

Ferrer: In addition to my counseling practice—which focuses on the design of more satisfying relationships—I taught graduate courses on sexuality and intimate relationships for almost two decades. Both my research and clinical experience led me to realize the intimate lives of an increasing number of people do not fit neatly into the established categories of "monogamy" or "polyamory."

Younger generations, in particular, are less concerned with labeling their relational identity and surveys show that millennials see monogamy and nonmonogamy as existing in a spectrum of fuzzy possibilities. Versus binary categories.

Personally speaking, I lived long periods of both monogamy and polyamory. At certain points in my life, I could no longer identify myself as monogamous or polyamorous. I felt I could live both relational styles without serious fears or conflicts. I was free to love one way or the other depending on the cards life threw at me.

My book does not aim to enthrone any particular relational style but rather acts to enhance people's relational freedom beyond the culturally prevalent forced choice between monogamy and polyamory.

You coined the term 'novogamy' in the book. Explain this concept and how it expands the mono/poly binary.

Transcending the mono/poly binary reveals a rich tapestry of relational options that I call "novogamy." Where "novo" equals new, and "gamy" equals union [from Latin and Greek derivations, respectively].

Here are a few examples:

First, developmental pulls can lead people to choose monogamy or polyamory as their most suitable relational style at different life stages. There is no universal sequence here: some people go from mono to poly, while others go from poly to mono. Still, others spiral through several mono/poly cycles throughout their lives.

Second, different cultural contexts, such as geographical places, gatherings or events, can impact relational behaviors. For example, some couples who are strictly monogamous at home give each other "free passes" when traveling or attending festivals such as Burning Man, held annually at Black Rock Desert in Nevada.

Third, as the great American poet Walt Whitman famously wrote, "Very well, then I contradict myself. I am large, I contain multitudes." And the image is pertinent here because many people mentally and emotionally want monogamy while sexually desiring a diversity of lovers. Or, like a poly researcher I know, others believe intellectually in polyamory but realize they can only be sexual with one person.

Fourth, consider the impact of modern technology. Through his 3D avatar, a client of mine has regular romantic encounters with many women—dinners in exotic places, erotic conversations, you name it—while in "real life" he is monogamously married to his partner. And, of course, it could be the other way around. You can be mono in the virtual world and poly in the physical world.

Finally, some people feel their identity has transcended the mono/poly binary and use new terms such as "novogamy" to describe their new relational style. And others reject all labels, which they perceive as limiting ideologies or conceptual boxes.

So, are you mono or poly? Well, it can depend on when you ask the question, where you are when you do it and what part of yourself you ask. And you can be both at the same time in different settings or have moved beyond the need to define yourself as either mono or poly.

But what about sexual fidelity? Would not this single factor cut the cake into mono and poly servings? Not so fast. Modern research shows that people understand fidelity and infidelity in drastically different ways. For some married couples, out-of-town or conference sex does not count as cheating, but for others pornography use, fantasizing about a third person or even close opposite-sex friendships—in hetero people, that is—are considered transgressions of the monogamous vow.

To complicate things, not everybody agrees that sexual fidelity is the qualifying standard for monogamy. For some, it is emotional fidelity—"monogamy of the heart" as it has been called—and still for others spiritual fidelity or soul union.

The takeaway here is that fidelity and infidelity are so differently demarcated that making any generic, clear-cut distinction between monogamy and non-monogamy becomes virtually impossible.

There has been a growing acceptance and prevalence of polyamorous relationships in the United States. Why do you think that is?

Well, on one hand, many couples who want to stay together are sabotaged by sexual habituation or incompatible sexual desires. At times, their opening into polyamory can be triggered by a clandestine affair; other times one or the other can develop a bisexual curiosity or even romantic feelings toward another person without sexual desire.

These and other factors encourage many couples today to explore polyamory.

On the other hand, feminists were among the first ones to make connections between monogamy and patriarchy. Although not all feminists are—or have to be—poly, it is interesting to observe that most of the main poly authors and activists are female. And in my couples counseling practice, it is often women who are today pushing to open their relationship…perhaps because men still cheat more than women.

Valuing their sense of freedom, autonomy and sovereignty, many contemporary women have less tolerance than before toward men seeking to control what they do or do not do with their bodies. That said, though polyamory can be deeply healing and liberating for a woman whose sexuality has been controlled by a jealous husband, it could be re-traumatizing for someone with a history of sexual abuse. Each case should be considered independently.

Many people will say they could never be in a polyamorous relationship because of jealousy. Discuss the role of jealousy in someone's decision to pursue this type of relationship.

Jealousy is a major roadblock to relational freedom not only in polyamorous but also in monogamous choices.

On the one hand, jealousy can prevent many individuals from living a poly lifestyle, as the thought of their partner loving or being sexual with anyone else can be emotionally unbearable. Over decades, countless monogamous men and women have told me that they would actually love to have other sexual partners or romantic connections, but they refrained from seeking them—because their current partner would then want to do the same, and they could not accept that outcome.

On the other hand, jealousy can affect non-monogamous relationships as well. At least some poly people may—consciously or unconsciously—select their lifestyle in order to minimize the stronger jealous feelings that a monogamous commitment to a single partner might elicit in them or to avoid partners with high levels of jealousy. Thus, decreasing jealousy can expand relational freedom independently of relational style.

This is why my book offers readers practical tools to transform jealousy into compersion—or empathic joy—so they can choose their relational style free from the grips of the "green-eyed monster" of jealousy, as Shakespeare once called this compulsive emotion [in his 1603 tragedy, Othello].