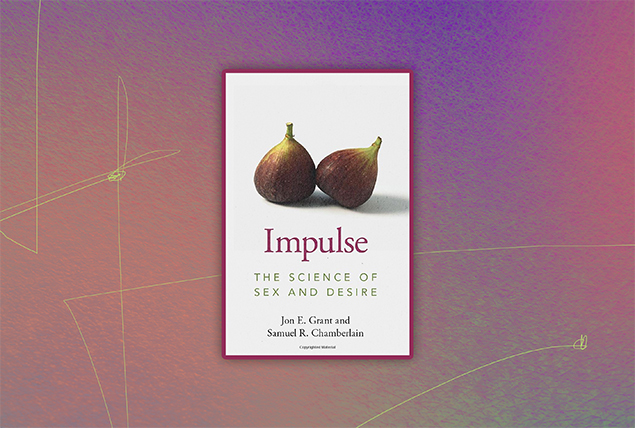

Between the Pages: 'Impulse' Discusses the Science of Sex and Desire

Sex is everywhere. Despite this, it's still largely regarded as taboo.

This beckons the question: How do we get accurate answers to sex-related inquiries when we're too uncomfortable to ask?

Psychiatrists Jon E. Grant and Samuel R. Chamberlain address common sex questions in their new book, "Impulse: The Science of Sex and Desire." Drawing on the latest research, this 250-page paperback, published by Cambridge University Press, aims to educate readers on a wide range of sexual concerns.

Grant, M.D., is a professor of psychiatry and behavioral neuroscience at the University of Chicago, where he conducts research on addictive, compulsive and impulsive disorders. In this Giddy exclusive interview, Grant discusses psychological factors that can impact sexual desire, compulsive sexual behavior, the benefits of a healthy sex life and more.

Editor's Note: This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Tell us about your background in sexual health and how it led you to write this book.

Grant: I see and treat people who have a variety of impulsive problems. Often, that entails some type of impulsive sexual behavior.

Before I came to the University of Chicago, I was a psychiatrist in the program on human sexuality at the University of Minnesota. There, I treated a range of sexual issues and found that sometimes in mental health, we have a fair awareness of sexual behaviors that are extreme. But when people ask about more typical behaviors of what might be considered typical this or typical that, it's really hard to have a lot of information. You only know when something is more problematic when you know what is more typical.

Samuel Chamberlain and I thought it would be good for folks to not have to go to "Dr. Google" to sort through all this information in order to find what is credible and what isn't.

We thought we could address—in bite-size nuggets—some of the major questions and issues people have raised to us over the years.

We really wanted to think about the major topics that come up when somebody thinks about sex. We envisaged a series of typical questions that people might want to ask, or would be too embarrassed to ask, but still might not know about.

We looked at research that's been peer-reviewed as opposed to just being put online. Not that things online might not be right, but we don't know if they are. We only know what the evidence tells us, and that would be peer-reviewed types of research.

What are some common psychological factors that can cause sexual desire to fluctuate?

I think desires fluctuate. Psychologically, one of the most common is if we have other competing variables that take up headspace.

If we're under a lot of stress—say we feel financially underwater—it's probably not the time to be thinking a lot about sex. Sex would be relegated to a less important fear at that point in our lives. And then, when things lighten up, the idea of sex and pleasure may take more of a prominent area in our brains and our lives.

If we have interpersonal stressors, whether we're dating or married but the relationship is having problems, sexual desire goes away. At other times, when things are going well, it may come back.

Then there's just our own internal state of who we are and where we are in life. When people feel good about themselves, they often feel more sexually desired, feel more confident about making overtures and try to get other people into their lives in intimate ways.

When we feel like we're having more problems, we feel less lovable and we don't think as much about intimacy and sex.

Many couples have mismatched libidos. What general guidance do you have for couples on how to manage that?

I think one of the most important things is for couples to discuss it.

If that's a problem, couples counseling can often show couples how to talk about their issues. There are also self-help books about how to talk about intimacy. I do think that if couples generally feel like they have a pretty open relationship with each other, they should be able to talk about things freely.

Sometimes, people feel embarrassed about it. And that can add to the stress of a potential mismatch. People will fill their minds with new narratives if they don't find out exactly what it is, but a lot of that can be soothed and eased by just being very honest with each other.

Most of the time, what couples will say is, "I've just been under so much stress at work and I didn't want to burden you with it. And that's why I don't even think about sex these days." Meanwhile, the other person has been thinking, "Oh, my goodness, they think I've gained weight and I'm no longer sexy."

Communication sounds so simple, but it's difficult.

There's debate over whether 'sex addiction' is an actual clinical condition. You call it compulsive sexual behavior (CSB) in your book. How do you make a diagnosis of CSB?

It's been a talked-about topic in mental health for decades. And it may still be a little bit unclear in terms of the best ways to diagnose it. As in what are the core features?

The consensus is that if you borrow from the substance world, the question becomes, "What makes somebody have an alcohol addiction versus just enjoying to drink a lot?" In the sexual world, that would be some of those same elements.

It's wonderful to enjoy sex and have as much sex as you want, right? So, it's not about the amount. It's more about [if] you feel driven to do it out of an almost uncomfortable compulsive need versus pure enjoyment.

For example, you're not getting to work on time or you're jeopardizing other relationships. Perhaps you're giving up all your social and leisure activities because sex is dominating your life. At that point, I think it would be worthwhile to take a step back and say, "OK, am I in control of this? Or is it controlling me?"

Sometimes that is a difficult fine line to draw.

In extreme cases, it's much easier [to diagnose]—in cases where people are looking at pornography so much that they're getting fired from their jobs, for example. The classic analogy is the person who drinks all day and has not gone to work for a few weeks.

I think when people are more functional, and yet it's still creeping into their lives at a greater level, it's useful for people to ask, "How much control do I have over this? Can I stop it for a period?" And if they can't, then it probably is much more of a compulsive problem.

In your book, you talk about the discussion about the dangers of sex—for example, unwanted pregnancy and STIs—rather than the benefits. What are a few key benefits of sex?

The great thing about sex is it does serve some wonderful purposes for us. It makes people feel excited. It gives a great deal of pleasure to people and uplifts their moods. People can find sex to be playful. I think it makes people feel vitalized, giving them more energy and reducing stress.

It creates, in some cases, human connections, which I feel, even if brief, help people deal with isolation or loneliness. Sex can be a real, pleasurable, beneficial piece to have in one's life.

Of course, people can use it in less healthy ways and it can be driven by other motivations. But I think, at its core, sex is a delightful thing for people to have when they feel like they want it. And they should have probably as much of it as they would like.