Have We Won the War on Drugs?

From supervised injection sites to Oregon's decriminalization laws, we're seeing evidence of a shifting scene on the many battlefronts of the so-called War on Drugs, which has been waged by the United States for the past half-century.

Officially, former President Richard Nixon called drug abuse "public enemy number one" on June 17, 1971. Since then, the U.S. government and various state agencies around the country have attempted to combat the prevalence of substance abuse in various capacities, with some tactics more effective than others.

More than 50 years since those words famously put illegal drugs directly in the crosshairs of American dogma, perhaps it's time to check and see how soon victory can be declared.

Casualties, survivor's guilt and trauma recovery

Like the veterans of any war, people who have experienced defeat at the hands of illegal drugs cope with trauma from personal loss, grief and simply coming into close contact with death, possibly many times over.

"Often, one of the very common traumas that I've seen among people who are addicts is that they lose people," said Karol Darsa, Psy.D., a licensed psychologist who wrote a book on trauma mapping and owns a trauma treatment center in Los Angeles. "There is a lot of death. They lose their loved ones, they lose their parents, their children—I mean there's constant death happening. Other things that are happening a lot, especially with heroin use, I've noticed, are people who overdosed but don't die but then their friends are trying to save them. So it's like really going through the trauma of saving somebody who is overdosing in front of you."

Darsa said survivors of these experiences often carry their guilt, memories and trauma with them literally and figuratively.

"I have an ex-heroin addict client who talks a lot about how they are carrying these naltrexone shots with them," she added, referring to a drug that blocks the effects of opioids. "They know that there's a risk somebody could almost die, or somebody could die, and so they have naltrexone shots and they basically give it to each other to save [one another]. And so she's been in that situation many, many times and, unfortunately, she did see people die, as well. So that in itself is a huge trauma that people often talk about in treatment."

Sadly, in this war, the casualties are often counted among family members and children of the afflicted.

Survivors of these experiences often carry their guilt, memories and trauma with them literally and figuratively.

"There's the trauma that a person who's an addict can cause to their family," Darsa noted. "The absence, the being out of their body all of the time, being preoccupied with using or fantasizing about when is the next time they are going to leave the kids at home and go out [to get drugs]."

Social, governmental and health initiatives since the 1980s and '90s have attempted to create support channels for parents dealing with addiction, and child services have increased the awareness of substance use as an element involved in child abuse or neglect. However, despite an increase in the awareness of drug use and its risk toward children and family members exposed to it, children still fall prey to the failings of addicted parents, both directly and indirectly.

"There's the risk of giving it to the children," Darsa said. "I have had many clients [whose] parents offered them drugs because they were using and so it was sort of part of the normal routine. For a child to grow up with an addict parent is hugely traumatic. It's basically not having a parent there.

"They might be barely physically there, and often there's huge neglect and there's abuse, because under the influence of a drug, a person can become violent, they can become physically or sexually abusive, or they can be completely lethargic and scare the children just because of their incapacity to do anything to care for the child," Darsa continued.

Not all addictions are passed on to children by way of direct transference. Even just denying a child's identity can be influential in factors that might contribute to their own addiction later in life. Recognizing the complexities and challenges of this situation is one of the critical aspects of working in recovery today, especially in marginalized and underrepresented populations.

Identity warfare in recovery

Inspire Recovery is an addiction and substance abuse recovery center in West Palm Beach, Florida, with a focus on serving transgender, queer and nonbinary people, as well as anyone in the LGBTQIA+ spectrum. Jaki Neering, L.C.S.W., the center's program director, maintained that affirming and holding space for a person's authentic self is critical to the work the center does when helping people address substance use issues in their own lives. Group counseling is an essential element of the program's recovery model, which results in a variety of benefits.

"At our center, when clients come in and they're able to talk openly about their LGBTQ experience, they might be able to say, 'Oh, and when I was 3 years old, I knew I was a little girl and everybody was telling me I was a little boy,' or whatever the experience," Neering said. "And then you see the head-nodding happening and you hear, 'Oh, yeah, me, too' and 'For me, this is what happened.' There's such a relatability and a normalizing that happens just in that, let's say, one interaction, for somebody to feel seen and heard and validated."

Inspire strives to create a safe and welcoming atmosphere for people struggling with addiction and people who identify as trans, nonbinary, gay or other lifestyles considered condemnable 50 years ago. It's taken more than 50 years, but substance use recovery is becoming a more inclusive field in the United States, little by little.

"It definitely normalizes and it creates mirrors and role models to look around and say, 'Oh, wow, that person is three months sober...she's working, I can do that, too,'" Neering explained. "It gives people hope, it's really reassuring, and they're building community."

Ending the war on drug-addicted people

Perhaps the greatest shift we have witnessed in the War on Drugs is that we now are beginning to recognize the drugs as the opposition, rather than drug addicts themselves.

Drug addiction is a condition, not a character flaw. Anyone can suddenly or slowly find themselves under the suffocating influence of medically prescribed pills, alcohol, illicit drugs or other substances.

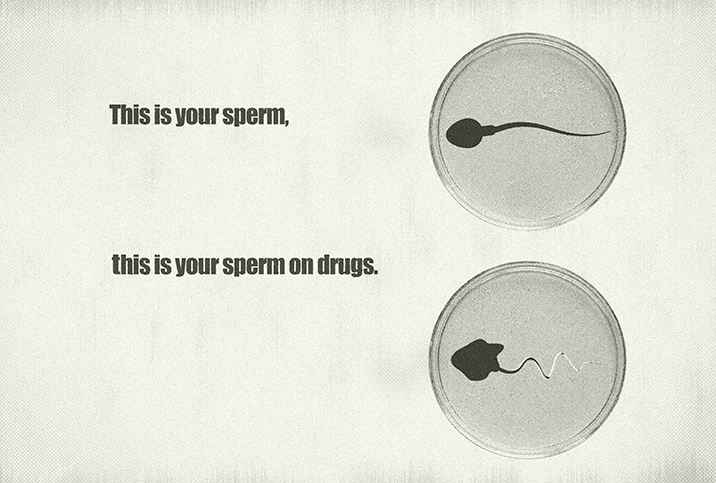

Past prevailing attitudes about substance use as an indicator of vice or character deficit not only prevented suffering people from receiving the help they needed, but also contributed to flaws in drug and alcohol education similar to those gaps we see in sex education in America. We're also still a bit confused about whether the bad guy is the corner-store drug dealer or the suit-wearing pharmaceutical executive.

We know we're still at war but we really don't know which direction to point our guns or our fingers. However, we know you can't beat disease by punching. You beat disease by tending to and caring for its victims.