The Authority on Sexual Health. We want to help readers take control of their sexual health with illuminating content that will enhance their quality of life.

By continuing use of this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

DISCLAIMER: THIS WEBSITE DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE

The information, including but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this Website are for informational purposes only. No material on this website is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this Website. See additional information.

By continuing use of this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

DISCLAIMER: THIS WEBSITE DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE

The information, including but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this Website are for informational purposes only. No material on this website is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this Website. See additional information.

Our Brands:

By continuing use of this site, you agree to the Terms of Use and Privacy Policy.

DISCLAIMER: THIS WEBSITE DOES NOT PROVIDE MEDICAL ADVICE

The information, including but not limited to, text, graphics, images and other material contained on this Website are for informational purposes only. No material on this website is intended to be a substitute for professional medical advice, diagnosis or treatment. Always seek the advice of your physician or other qualified healthcare provider with any questions you may have regarding a medical condition or treatment and before undertaking a new healthcare regimen, and never disregard professional medical advice or delay in seeking it because of something you have read on this Website. See additional information.

© Copyright 2025 Giddy® | All Rights Reserved.

© Copyright 2025 Giddy® | All Rights Reserved.

Daliah Singer

First, there's the crib. And the just-right rocking chair. Then come the swaddle blankets printed with adorable forest creatures, the onesies with clever taglines, and your favorite books from childhood to pass along to a new generation. Having a baby is expensive, yes, but at least these credit card swipes are for the fun stuff.

What many soon-to-be parents don't realize is how much the cost of pregnancy—not the baby goods, but the medical side—is going to set them back. More than 3.6 million babies were born in 2020 in the United States, costing upwards of $50 billion, according to reporting by the New York Times. Pregnancy, childbirth and postpartum care are the main reasons women actually utilize their health insurance plans—except their insurance plans aren't covering the entire bill.

Families themselves are shelling out a lot of those dollars. On average, an uncomplicated vaginal birth costs between $5,000 and $11,000, while C-section births range from $7,500 to $14,500, according to data from FAIR Health, a New York City nonprofit organization that collects information about healthcare costs.

"The range is quite broad. Some people with commercial coverage walk away with hardly any financial liability, and [for] others, it adds up to a lot," said Carol Sakala, Ph.D., director for maternal health at the nonprofit National Partnership for Women & Families in Washington, D.C. "It's really difficult to predict."

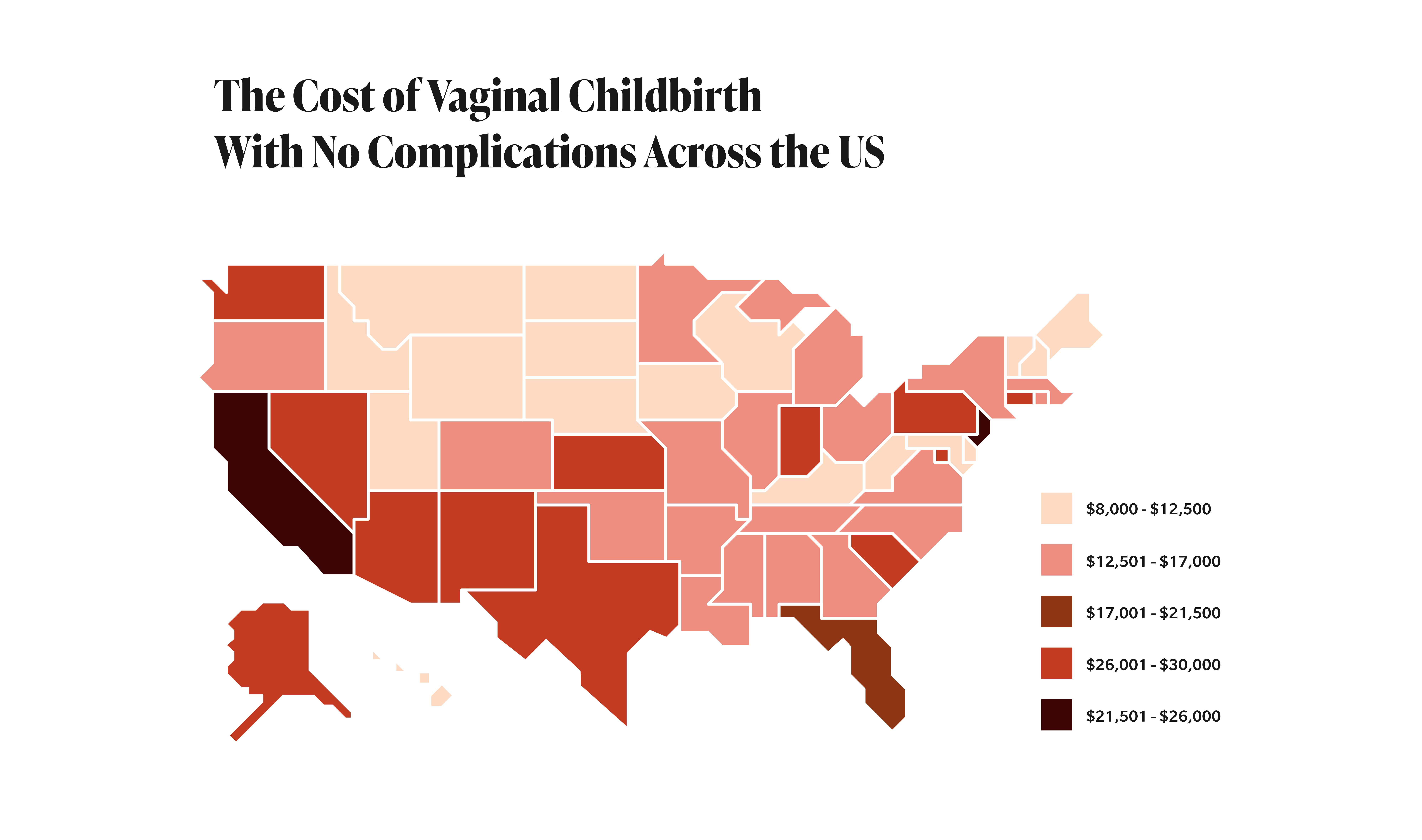

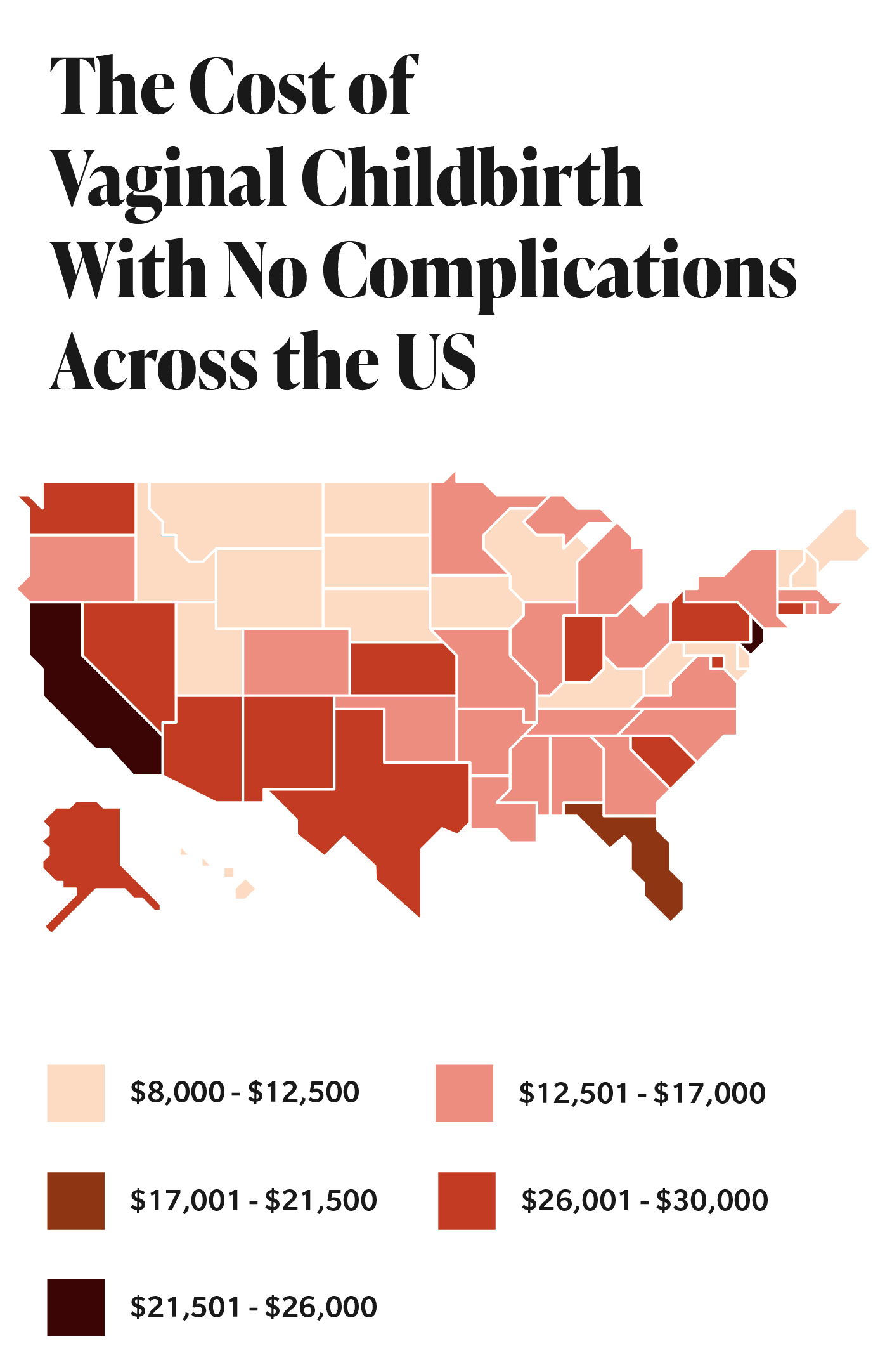

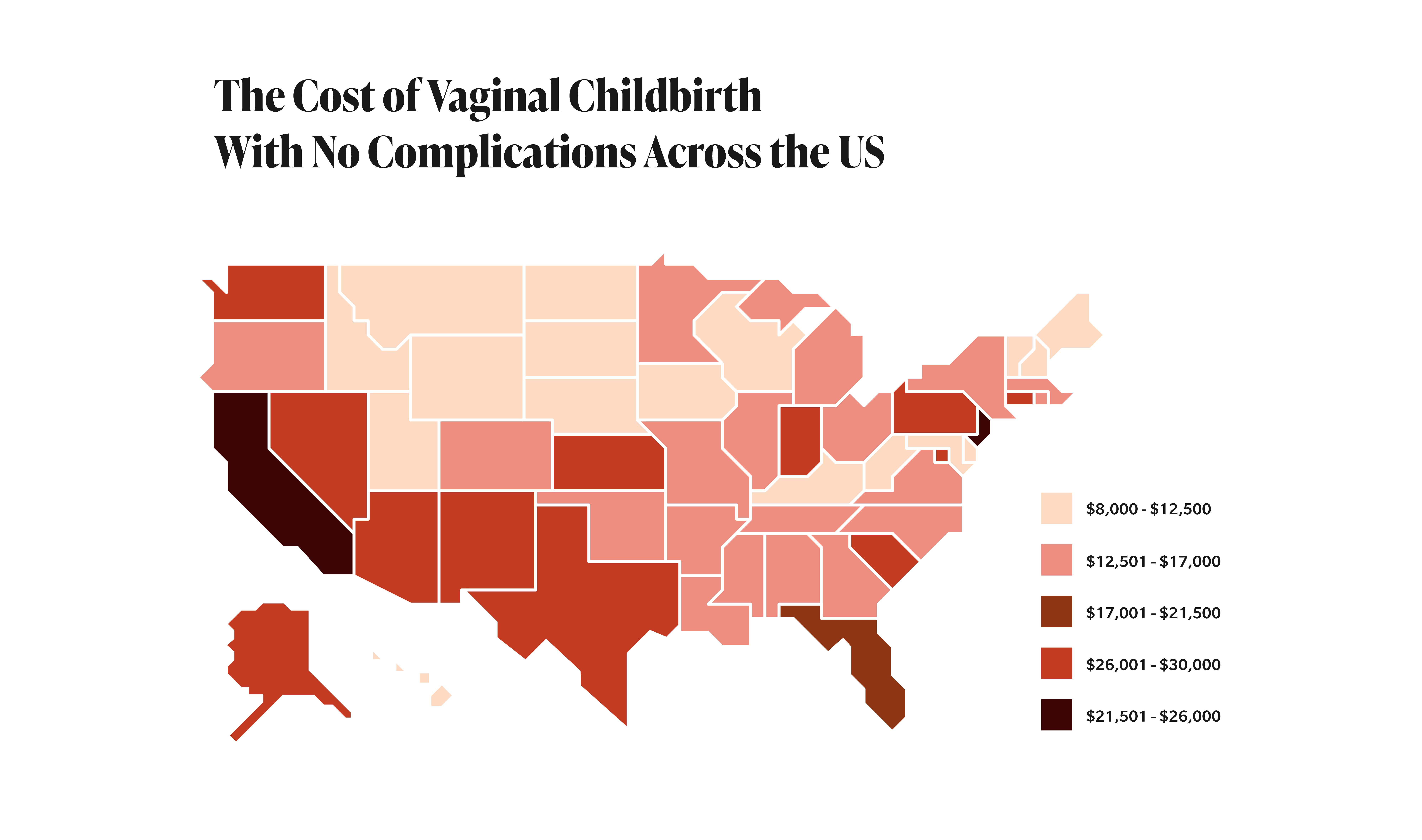

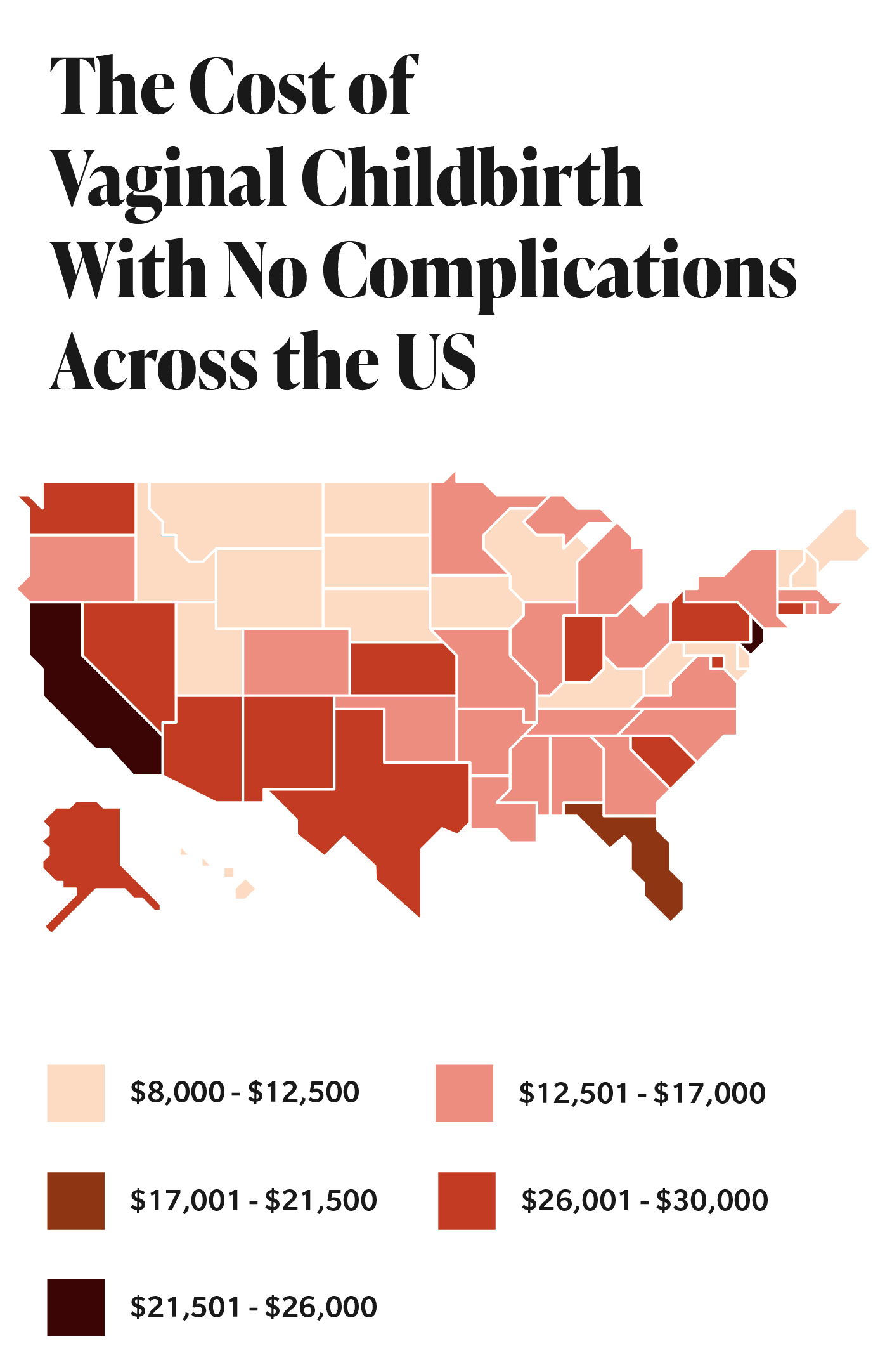

Totals largely depend on where you live, what insurance you have (if any), and where you go for care. There is widespread variation in the cost of childbirth in the United States, ranging from $8,361 in Arkansas to $19,771 in New York, with actual out-of-pocket costs fluctuating by state, too, stated a 2020 study by the Health Care Cost Institute, located in Washington, D.C.

What is clear is that births are emptying families' wallets more than ever. The average out-of-pocket spending for maternity care among women with employer health insurance jumped 49 percent, from $3,069 to $4,569, between 2008 and 2015, the most recent year for which statistics were available, according to a 2020 study of 657,061 women published in the journal Health Affairs.

"In the same period, mean total out-of-pocket spending for vaginal birth increased from $2,910 to $4,314, and for cesarean birth, it increased from $3,364 to $5,161," the report stated. These amounts cover the 12 months before delivery through three months postpartum and include only the cost for the mother's care.

Totals largely depend on where you live, what insurance you have (if any), and where you go for care.

When incorporating newborn care into the numbers, privately insured families paid about $3,000 out-of-pocket for maternal and newborn hospitalizations between 2016 and 2019, according to a study published in July 2021 in the journal Pediatrics. This total rose by $1,000 or more when C-sections and/or neonatal intensive care was involved.

"The standardized costs of maternity care remained stable over this time period, so that suggests health insurance plans are shifting a larger proportion of costs to the people," said Michelle Moniz, M.D., the study's lead researcher, an OB-GYN, and an assistant professor in the department of obstetrics and gynecology at the University of Michigan who is also affiliated with its Institute for Healthcare Policy & Innovation.

"The implication of that is we, as a society, are saying it is okay for a family with a newborn and maybe other children at home to go home with a $5,000 bill for that care," she said. "But medical debt is a risk factor for all-cause mortality. It can lead to poor health outcomes. There are ethical considerations here around whether we want to be a society that is saddling [families] with this kind of financial sticker shock just for having a baby."

The good news: Pregnancy—including prenatal, inpatient and postnatal care—is now covered by all major medical insurance plans. Before this coverage became mandatory in 2014 under the Affordable Care Act (ACA), only nine states required maternity coverage, and less than 15 percent of individual health plans included pregnancy on its list of covered benefits.

On a more frustrating front, though, these plans have loopholes. Beyond the monthly premiums people pay to have health coverage, insurance companies can charge copayments, deductibles and coinsurance rates for maternity and newborn services. Moniz's study pointed to rising deductibles—the amount you're required to pay for covered services before your insurance provider takes over—as the key culprit in the increasing out-of-pocket costs. The annual out-of-pocket maximum for a family utilizing a commercial-based plan in 2021 was $17,400, she said.

Medicaid, the state and federal healthcare plan for people with low incomes, finances around 43 percent of births in the country, according to the Medicaid and CHIP Payment and Access Commission. Medicaid is legally prohibited from charging out-of-pocket fees for most pregnancy- and infant-related care. But many low-income women are covered by employer-based plans rather than Medicaid, so they're also bearing the burden of escalating out-of-pocket costs, Moniz noted.

"About 20 percent of people living in lower-income households…are covered by these [private] plans when they undergo childbirth," she said. "These plans are not creating a financial burden just for middle-class or affluent people. They have far-reaching consequences for socioeconomically marginalized groups."

The extreme ranges in average expenditures noted in the research don't necessarily help women or families truly prepare for the financial burden of having a baby. To understand what having a baby actually costs the average mom, from when she finds out she's pregnant through her final postpartum appointment, Giddy spoke with three mothers who live in the Denver area. (Colorado has some of the highest out-of-pocket costs for childbirth.) All of them had private health insurance, through either an employer or university, throughout their pregnancies and births. In fact, they all gave birth at the same hospital. But their experiences—and their bills—varied greatly. These are their stories.

Beyond some nausea during her first trimester, Jessica had what she called a "straightforward" pregnancy. But that didn't mean the birth of her first child, a son, was cheap. Two early screenings—one for genetic testing on the fetus, one to make sure she wasn't a carrier for any genetic disorders—cost $249 each and, through some quirk in the system and a cash-pay discount, were cheaper to pay directly than to submit through insurance. Jessica opted for the blood tests rather than a covered amniocentesis because the latter screening carries a risk of miscarriage. Her insurance would foot the bill for the blood tests only if she was age 35 or older or had specific risk factors, and she was only 34 at the time.

Jessica's highest copay, $150, was for a fetal movement check close to her delivery date, when she was worried because she hadn't felt her son stir in a while. All turned out to be fine.

After doing her research, Jessica planned to have an unmedicated birth in the birth center attached to the hospital. She signed up for the available doula program for $450, which covered an initial consultation and 10 hours in the delivery room and was less expensive than trying to find a doula privately. Hiring a midwife or opting for a birthing center can generally lower overall costs, in part because women who utilize these services are less likely to receive pain-relief medications or undergo a C-section, according to the American Pregnancy Association. Home births using a midwife reduced costs by an average of $2,541 (in Canadian dollars) when compared to physician-assisted hospital births, a 2015 study published in Plos One found. And a 2018 New York Times article noted that "the cost of a birth center delivery is roughly half that of an uncomplicated hospital birth."

Jessica eventually opted for an epidural following nearly 24 hours of active labor. In total, her insurance carrier was charged almost $44,000 for the birth alone, for which Jessica paid around $1,500. One of the most significant charges, after the hospital fee, was $7,770 for an out-of-network anesthesiologist. This occurred even though she was at an in-network hospital.

"How was I supposed to check if the anesthesiologist they sent in—when I was 8 centimeters dilated and had been having contractions every five minutes for 24 hours and finally gave up trying to go sans meds—was in-network?" said Jessica, who wound up paying $255 after insurance for the anesthesiologist's services.

This practice is known as surprise billing, when a patient is charged for out-of-network care at an in-network facility. Close to 1 in 5 privately insured families receive one or more of these bills for mother or newborn care, per research published in JAMA Health Forum. The maternity-related service most often associated with surprise charges is anesthesia, as it was in Jessica's case, though she paid less than the $744 median estimated liability that researchers uncovered.

"You will encounter sky-high fees from somebody who doesn't happen to be in your network or in your plan, and you didn't have any choice because you didn't engage that person—that was the person who happened to be at the hospital that day," Sakala said.

The No Surprises Act was introduced in Congress in 2019 to stop this type of charge. It passed at the end of 2020 and goes into effect on January 1, 2022.

Jessica couldn't check for any other odd charges on her bills because nothing was itemized, she said. Not that she had the time to dig too deeply once they started arriving—both she and her husband were back at work full-time while trying to care for a newborn.

In 2018, however, one father in West Virginia did manage to track down detailed charges. He published an essay in the Conversation outlining the fees, which included everything from a pair of Tylenol tablets ($25) to 48 hours of room and board for his wife ($3,100) and son ($1,500), to a baby hearing test ($260).

In 2016, following his wife's C-section, another father posted a bill on Reddit that included a $39.35 fee for "skin-to-skin" contact post-delivery.

Jessica ended up paying almost $2,750 for all of her pregnancy- and birth-related medical bills. She and her husband both maxed out their flexible spending accounts (FSAs) when they found out they were pregnant, which helped cover a lot of the expenses without draining their bank accounts.

"I was honestly more surprised by how little we had to pay for, which I think is just a result of having good insurance," she said. "We're very lucky that none of this was a super financial burden on us."

A behavioral health specialist at a family practice, Morgan is more familiar with the healthcare system than most people. But she still felt as though she'd been thrown onto a roller coaster when, at her 20-week appointment, her OB-GYN told her and her husband that their baby's head was small. They were referred to a doctor specializing in high-risk pregnancies, and two weeks later, the doctor called and said they needed to come to the office right away.

An amniocentesis, a procedure that tests for chromosomal abnormalities and fetal infections, ruled out genetic issues. Unfortunately, the procedure was not covered by her insurance.

Still, she had to drive across town every two weeks for a Doppler ultrasound and growth check. Around 30 weeks, Morgan received steroid injections (costing about $200 total) to help prepare her body for an early birth, then she started seeing her high-risk and regular OB-GYNs on a weekly basis. The high-risk OB-GYN cost an average of $464 per appointment, compared to an average of $180 for her regular doctor.

Labor was induced shortly after she passed the 36-week mark. At the hospital, a balloon was used to dilate her cervix. She received an epidural. She was administered Pitocin to induce labor. The baby reacted poorly, and Morgan was rushed to a surgical unit for a C-section.

"The plan was that the baby was going to be small—he or she was going to be in the NICU," Morgan said. "No one ever talked to me about the possibility of a C-section."

Her daughter was born healthy in April 2019, and, thankfully, she didn't need to stay in the NICU after all. But because of the surgery and her small size, the new family opted to stay in the hospital for an additional night—three nights total following the birth.

In all, they doled out about $5,500. Morgan recalls that $1,000 or less was for the birth itself, because they had already hit their maximum out-of-pocket expenses with all of the additional appointments and tests.

In 2014, Kate was pregnant with her first child and having a pretty easy go of it. She went on daily runs and attended weekly yoga. So she was startled when she suddenly started gaining extra weight—her hands and wrists were also painfully achy. At her 32-week appointment, the OB-GYN diagnosed Kate with high blood pressure. (Though they utilized the same health insurance carrier, Jessica's prenatal visits were covered, while Kate paid $25 to $50 in copays each time.)

She was taken across the street to a hospital, where she remained for a couple of days before being advised to self-monitor at home. A specialist to whom Kate was referred diagnosed her a few days later with preeclampsia, a condition that can be life-threatening for both moms and babies. It was all so stressful that Kate soon had her husband drive her back to the hospital so professionals could keep an eye on her and the baby.

At 35 weeks, Kate underwent an emergency C-section. Her son weighed less than 4 pounds when he was born. He stayed in the NICU for three weeks before they were able to head home. During that time, he needed light treatment for jaundice and craniosacral therapy, which cost between $75 and $100 for each of the four or so sessions.

Kate recalled that her total hospital bill was around $200,000. She paid close to $8,000 to meet the family deductible, plus an additional $25 per night for the separate wing she moved into for almost three weeks to stay close while her son was in intensive care.

Families should remember that pregnancies often span two health plan years, Sakala noted, so the deductible owed may be twice as much as originally expected.

Kate's bill was particularly high because of the extended stays for her and her son. The facility fee for the mom's hospital stay is the single-largest charge throughout pregnancy, Sakala said. About four out of five of all dollars paid on behalf of the mother and the baby across this whole time frame, from discovering you're pregnant through eight weeks postpartum, are going into that small window of one to two days women spend in the hospital, she said, adding that care for the baby alone accounts for more than one-third of all the costs paid.

As C-sections have become more common in recent years, they've also become more costly. In 2019, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported that C-sections account for nearly one-third of U.S. births. Sakala said payments for C-section deliveries are about 50 percent higher than those for vaginal births. Moniz's study found the average out-of-pocket C-section cost for women with employer insurance was $5,161, nearly $1,000 more than for vaginal deliveries.

Kate was surprised by her final bill and said she never realized how expensive it was to have a baby.

"I remember my mom being like, 'What? It cost $5 to have a baby [when I had you],'" she said. "It was pretty shocking."

Distracted by diapers and sleepless nights, new parents often don't have time to review bills in detail to make sure they actually received every service for which they were charged. And the bills sometimes take months to arrive, with some contradicting each other or not reflecting earlier payments. On a call with the hospital after noticing discrepancies between the online portal and the paper bills she was receiving, Jessica was told services just get "miscategorized" sometimes.

Up to 40 percent of hospital insurance claims have errors, a 2009 University of Minnesota study found.

"There are standard things that [providers] might be assuming you'll use but you said you don't want," said Sakala, who recommends parents request itemized bills to verify that the amount they're shelling out is correct.

Morgan never saw an actual bill from her daughter's birth. The couple's personal information was entered incorrectly into the system, and all of their paperwork was sent straight to collections, another complication she had to sort out.

Overall, she's astounded that she didn't end up paying more because of all of the complications and extra visits, and she's still not sure if that's because of her insurance or because of the mix-up with her paperwork. She also remains frustrated with how obtuse the system is for all mothers.

"Nobody talks about the cost of anything. It's not like they're sitting there with this menu: For a C-section, it's going to [cost] this," Morgan said. "Your pregnancy is always going to be a surprise. No one can really prepare you for what the cost is going to be."