What Are the Ultimate Goals for the State of Sexual Health in America?

The United States Supreme Court decisions in Roe v. Wade on January 22, 1973, and the subsequent Dobbs decision on June 24, 2022, are notable turning points in the history of sexual and reproductive health in the U.S.

But they are far from the only landmarks.

In 1972, for instance, the Supreme Court ruled in Eisenstadt v. Baird that unmarried people could access contraception methods. In 1998, the "morning-after pill" was approved as an over-the-counter emergency contraception method.

In 2012 the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first PrEP medication for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevention.

The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) announced that, between 1991 and 2020, the teen pregnancy and birth rate decreased by 75 percent.

Yasaman Ahmadieh, D.O., M.P.H., an adolescent medicine physician in Denver and a fellow at Physicians for Reproductive Health (PRH), said she is glad that—thanks mainly to increased education and contraception availability—people are able to make more informed decisions about their bodies and lives.

However, she noted there is still much to do to address remaining and emerging challenges and set new standards in sexual and reproductive healthcare.

In 2021, the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine (NASEM) released a consensus study report outlining several focus areas for promoting sexual health in the U.S.

Vincent Guilamo-Ramos, Ph.D., M.P.H. is the dean and Bessie Baker distinguished professor at the Duke University School of Nursing, a member of the Presidential Advisory Council on HIV/AIDS (PACHA), and he has served as a member of the NASEM committee and chairman of the board of directors at Power to Decide.

He combed through the report to develop a plan.

Guilamo-Ramos drew five key action areas from the report that could guide the nation's efforts to improve sexual health in the next decade and beyond:

- Adopt a national sexual health paradigm.

- Make sexual health everyone's responsibility.

- Prioritize sexual health promotion for adolescents and young adults.

- Get parents and families involved in sexual health.

- Address the social determinants of sexual health.

Additionally, Susan Gilbert, M.P.A., a co-director of the National Coalition for Sexual Health (NCSH), identified six specific areas of focus:

- Decreasing sexual violence

- Decreasing the number of unintended pregnancies

- Diminishing the risk and prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs), including HIV

- Increasing access to affordable, high-quality sexual health services

- Increasing access to comprehensive, medically accurate sex ed nationwide

- Reducing cervical and other HPV-related cancers

Here's a look at how these objectives intertwine and how they can be achieved.

Currently, the U.S. approaches issues of sexual and reproductive health with a focus on risk, disease and the potential negative consequences of sex, Guilamo-Ramos explained.

"The NASEM committee advocates a departure from the current risk-focused paradigm toward adoption of a sexual health-focused model that takes a holistic view of sexuality as an important facet of health and well-being," he said.

In moving toward a more expansive sexual health approach, it will be essential to increase recognition of structural and societal factors that contribute to sexual health rather than solely focusing on individual behavior, he continued.

A study published in March 2023 in Frontiers in Public Health affirmed NASEM's proposals.

"We seem to focus on single issues like STIs, HIV or domestic violence, which are serious public health issues. Many of these problems occur in the same individuals and subpopulations," said Eli Coleman, Ph.D., a professor emeritus and the former director of the Institute for Sexual and Gender Health at the University of Minnesota Twin Cities, who co-authored the study.

"These issues are part of a syndemic—an epidemic of epidemics, which means you need a systematic and more holistic approach to address the underlying issues—and many of these relate to difficulties related to sexuality," he explained.

Public health agencies have often been funded and tasked to prevent disease rather than promote overall health and well-being, Coleman added. This can make a coordinated approach challenging since different health conditions have separate funding streams, sometimes leading to siloed programs.

As part of their research, Coleman and his cohorts collaborated with experts from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to determine specific indicators to measure sexual health outcomes.

The recommendation was to use such markers to establish a comprehensive scorecard that various entities throughout the public health system can utilize. Guilamo-Ramos and Coleman said the scorecard would go beyond tracking adverse sexual health outcomes to incorporate multiple components that influence sexual health.

Guilamo-Ramos noted that a national sexual health index could track the following:

- Availability and use of comprehensive sexual health services

- Healthy, safe and consensual sexual relationships

- Incidence of adverse sexual health outcomes, which remains elevated in the U.S. today

- Trends across measures of population-level sexual health knowledge, communication and attitudes

Only a small sector of the healthcare workforce is responsible for sexual health, Guilamo-Ramos noted. That narrow focus is a missed opportunity, as involving more stakeholders could help to address sexual health more holistically.

The NASEM report suggests sexual health should be integrated into routine primary healthcare to expand accessibility and improve outcomes. Guilamo-Ramos said nurses, pharmacists, behavioral health professionals and other allied health professionals could contribute to the cause, too.

"Nurses, in particular, hold a tremendous untapped potential for supporting an expansion of the workforce to take ownership and responsibility of sexual health promotion," Guilamo-Ramos said. "At more than 4 million, nurses account for the largest sector of the healthcare workforce. Importantly, nurses are highly skilled, deliver the vast majority of all direct patient care, and by a wide margin, represent the most trusted profession in the U.S. for more than 20 years in a row.

"In leveraging nurses, the U.S. can take important steps toward significantly scaling up efforts to achieving nationwide sexual health."

Various entities outside the healthcare sector could also help promote better public sexual health, including:

- Families

- Schools

- Faith-based organizations

- Workplaces

These communal efforts could help the U.S. achieve goals that include diminishing rates of sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) such as chlamydia, gonorrhea and syphilis, which have surged in the past few years.

"These are [diseases] that are treatable and preventable, but there can be grave consequences if they aren't treated," said Rachel Deitch, the federal policy director of the National Coalition of STD Directors in Washington, D.C. "Curbing sexually transmitted infections could be an easy win if we put funding into very basic and effective prevention strategies like public awareness and education, testing and treatment, and outbreak response."

Congressional funding for prevention programs has decreased measurably, she added, while rates have increased. Plus, the federal government doesn't offer a dedicated clinical services program like it does for family planning services or HIV treatment.

Similarly, Fred Wyand, the director of communications for the American Sexual Health Association (ASHA) and the National Cervical Cancer Coalition, has ideas for how to make improvements.

Between 2005 and 2019, the number of overdue cervical cancer screenings rose from 14 percent to 23 percent, greatly due to lack of awareness about screening tests and one's need to have them.

More preventive care, including broader human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine access and cancer screenings, could help curb cervical and other cancers prevalent throughout the U.S., Wyand explained. High-risk strains of HPV are associated with various cancers, and it's estimated that there are more than 37,000 HPV-related cancers in the U.S. annually.

Most people will be infected with HPV at some point, per the CDC. While most cases are benign and clear up naturally, vaccination and testing are crucial to safeguard against potentially serious harm.

An important goal of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) is to immunize at least 80 percent of young people against HPV by 2030, Wyand noted. Data from 2021 indicates about 61 percent of teens ages 13 to 17 are up to date, a notable increase from a few years prior.

"We're on the right track, but the next decade will be here in a flash and it's crucial we continue to build on—and improve—this momentum," he said.

It's not all bleak, though.

"There's reason for optimism, as 75 percent of those assigned male gender at birth have had at least one shot in their HPV vaccine series, and 79 percent of those assigned the female gender have started their vaccine series," Wyand said.

There is work to be done regarding cervical cancer screening, according to Wyand. National Cancer Institute (NCI) data indicated that people with cervixes are increasingly missing screenings.

"Between 2005 and 2019, the number of overdue visits rose from 14 percent to 23 percent. The top reason given for not being screened? Simple lack of awareness about screening tests and one's need to have them," Wyand said. "Most HPV-associated cancers can be prevented, and with cervical cancers, the two-pronged approach of vaccination and screening means virtually no one should develop the disease."

Moreover, expanded sexual health resources and availability and shared responsibility can decrease the number of unintended pregnancies, explained Rachel Fey, the vice president of policy and strategic partnerships at Power to Decide in Washington, D.C. In addition, the combination can improve maternal and infant health outcomes.

Shared responsibility for sexual and reproductive health services could also improve access to contraception and abortion services, two other priorities indicated by both Ahmadieh and Fey.

"A full spectrum of reproductive health includes family planning, prenatal care, contraception, STI screening and treatment, and abortion," Ahmadieh said.

Among other means, she and Fey suggested boosting funding for the Title X Family Funding Program, advocating for legislation such as the Women's Health Protection Act, making contraceptives available over-the-counter, and expanding telehealth services.

"It is necessary and essential to support passing these policies to prevent further increase in health inequity," Ahmadieh said.

A more expansive and diverse array of health-promoting services and providers may also help to diminish sexual violence by increasing opportunities for prevention and intervention.

"In this past decade, particularly due to the widespread impact of the #MeToo movement, the U.S. has had a cultural reckoning surrounding issues related to sexual assault. This has influenced individuals and the systems they reside in, whether they're schools, employers or community centers," said Halle Nelson, a communications specialist at the National Sexual Violence Resource Center in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

It is now more common to see sexual violence-related curricula during orientations at colleges and workplaces, she said. There are also widespread changes, such as the Speak Out Act and Ending Forced Arbitration Act.

"When people have a greater understanding of sexual assault as an issue, when they feel less stigmatized discussing it, and when they know the full degree of their rights and choices if they experience an assault, they are in a healthier space to advocate for themselves, for their bodies and for their community members," Nelson explained.

Adolescents and young adults are a "key national priority," Guilamo-Ramos said, noting that these demographics experience a disproportionate share of adverse sexual health outcomes.

For example, he said teens and young adults account for approximately half of all new STI diagnoses, despite the fact this demographic represents about one-quarter of the nation's sexually active population.

Additionally, teen parenthood rates in the U.S. are significantly higher than in other high-income countries.

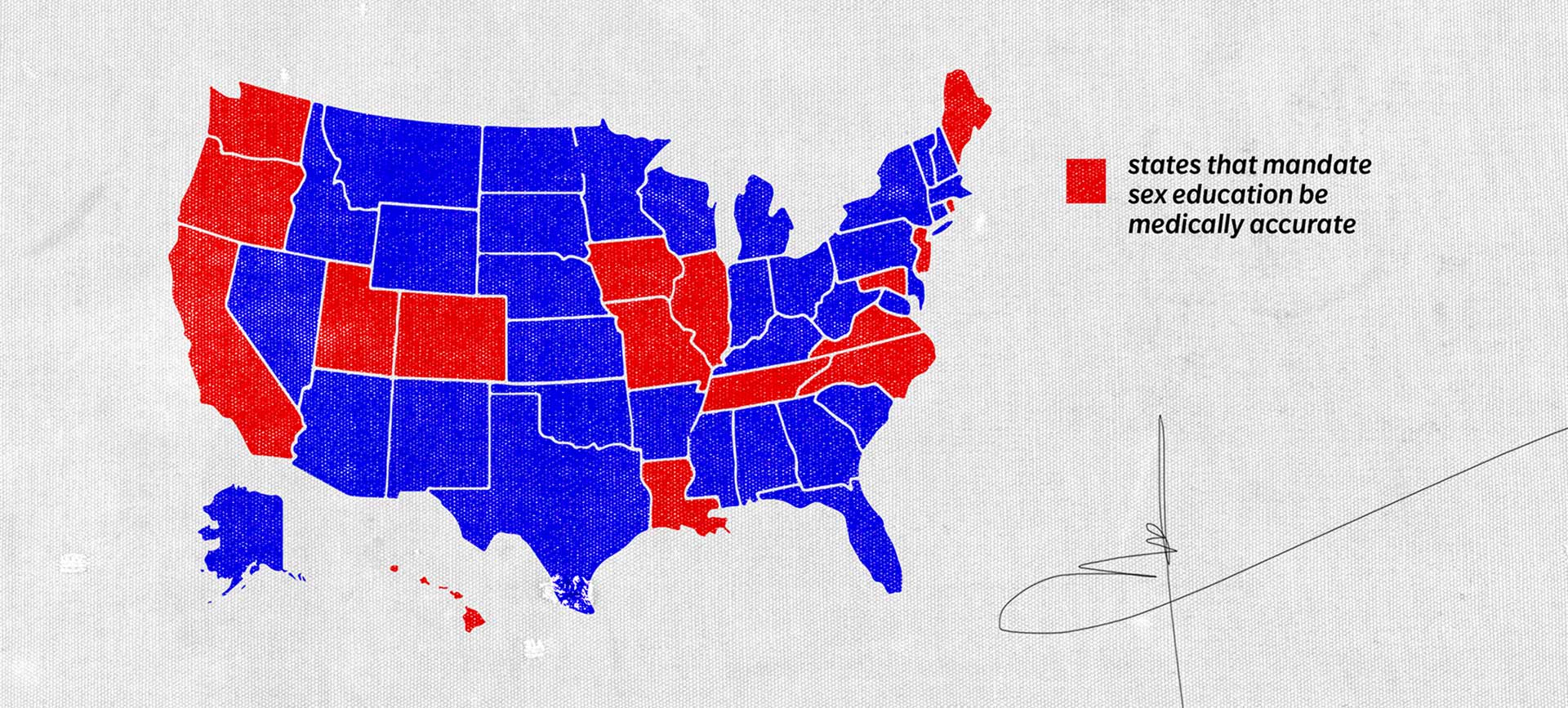

"However, for many adolescents and young adults, there are substantial barriers to comprehensive sexual health education and sexual health services. For example, only 17 states mandate that sex education be medically accurate, and in 18 states, healthcare providers are allowed to inform parents of received STI services without minors' consent," Guilamo-Ramos said.

Ensuring adolescents and young adults have access to crucial care is vital to improving the nation's sexual health as a whole. That's according to Alison Macklin, M.S.W., the policy and advocacy director for SIECUS: Sex Ed for Social Change (formerly the Sexual Information and Education Council of the United States) and an adjunct professor at the University of Denver, and John Santelli, M.D., M.P.H., a professor of population and family health and pediatrics at Columbia University in New York City.

This care would include gender-affirming care, abortion and contraception access, and STI testing.

Another step forward is improving sex education.

Santelli said most mainstream medical organizations, including the Academy of Pediatrics, the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) and the Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine, support these goals, as do most Americans.

According to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey 2021, nearly one-third of high school students had had sex, while 21 percent were currently sexually active, Ahmadieh noted. Yet, many schools continue to teach abstinence-only principles, which research indicates are ineffective and discriminatory.

Such a curriculum doesn't convey information about key sexual health concepts, including contraception, STDs and STIs, consent, sexual orientation and gender identity. It also stigmatizes sexual activity and encourages guilt, shame and judgment, she added.

"The goal of comprehensive sexuality education is to nurture adolescents' social and emotional development. It should address social, emotional, biological and medical aspects of sexual and reproductive health during adolescence," Ahmadieh said. "Furthermore, it should encourage positive attitudes and skills toward sexuality and engaging in sex."

Comprehensive sexuality education doesn't leave anyone out. It includes education for all teenagers and doesn't discriminate based on their gender, sexual orientation, race/ethnicity, language, immigration status, religion and physical disabilities, Ahmadieh added.

"A comprehensive sexuality education will help adolescents to develop skills to have healthy relationships, safe sexual activity and plan preventing of pregnancy or having children," she continued.

Moreover, comprehensive sex education classes that include discussion of consent can decrease incidents of sexual assault, according to SIECUS and Winona State University.

Rates of sexual violence and harassment have increased among young people, particularly females, according to the CDC. Yet, most states do not require consent education as part of the school curriculum, per a report by Winona State University.

"In addition to learning about STIs and unintended pregnancies, young people should learn about sexual assault, how to protect themselves and how to identify sources of support," the SIECUS website states. "Research shows that comprehensive sex education can help prevent sexual assault."

To improve sex education and healthcare for teens, Santelli recommended parents attend school board meetings and advocate for young people's rights and well-being in the community.

At a state level, he noted that ensuring schools follow the National Sex Education Standards and passing acts such as the Real Education and Access for Healthy Youth Act can help make better sex ed a reality. And voting for legislation to protect young people's civil liberties can preserve or improve access to care.

Fey added that federal legislation and programs like the Teen Pregnancy Prevention (TPP) Program and Personal Responsibility Education Program (PREP) are similarly helpful.

Research has shown parents are integral to influencing adolescents' decisions about sex, Guilamo-Ramos explained. As a result, the NASEM report advocates increasing efforts to involve parents in adolescent sexual health promotion.

Traditionally, most programs aimed at improving adolescent sexual health outcomes targeted teens directly, while few are designed to help parents better support their children.

"It's important to note that evidence-based and effective programs for engaging parents in adolescent sexual health promotion exist," he said.

One example is Families Talking Together (FTT), a parent-based program he noted has proven effective for improving adolescent sexual behavior and health outcomes. It is part of the HHS's national Teen Pregnancy Prevention program and is highlighted in the NASEM report and by the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF).

"Broad, national scale-up of FTT and similar evidence-based parent programs for sexual health promotion would add a novel element to the existing mix of adolescent sexual health programming and can have an outsized impact," Guilamo-Ramos said. "Families, and parents in particular, can also be leveraged to address stigmas that continue to be associated with issues of sexual health."

There has been support for large-scale national efforts to equip parents with evidence-based guidance for developmentally appropriate, comprehensive sexual health communication, Guilamo-Ramos continued, adding that sustainable funding mechanisms must be established to deliver programs at scale.

Finally, in order to improve sexual health for all people, Guilamo-Ramos and the NASEM committee stressed the importance of recognizing structural and societal factors as drivers of sexual health inequities and addressing these issues as part of a holistic approach.

"Efforts to mitigate the negative impacts of harmful social determinants of health represent a key sexual health priority," Guilamo-Ramos said.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines social determinants of health as "nonmedical factors that influence health outcomes." These conditions, forces and systems include but are not limited to social policies and economic and political systems.

Examples include the following:

- Employment and income security

- Food and housing security

- Education

- Early childhood development

- Social inclusion or discrimination

- Access to affordable, quality health services

According to the CDC, health equity is a state in which everyone has a fair and just opportunity to attain their highest level of health. Health inequities represent the opposite.

"There are longstanding and persisting sexual health inequities, with communities and populations affected by harmful social determinants of health experiencing disproportionate negative sexual health outcomes," Guilamo-Ramos said. "Therefore, it's crucial to consider both measures of overall sexual health and measures of sexual health equity when evaluating progress and success in advancing the national sexual health paradigm."

Achieving health equity, per the CDC, requires:

- Addressing injustices

- Overcoming systemic obstacles to health and healthcare

- Eliminating preventable health disparities

Preventable health disparities "are preventable differences in the burden of disease, injury, violence, or opportunities to achieve optimal health that are experienced by populations that have been disadvantaged by their social or economic status, geographic location and environment," according to the CDC.

"I think it's important to acknowledge that people don't lead siloed lives and siloed solutions alone will not work," Fey said. "We need to think broadly about the environments in which people make decisions—or lack the ability to make decisions—about their reproductive health and well-being and how we can build systems that better support them."

In addressing health inequities, it is imperative to emphasize focusing on people who belong to multiple marginalized groups, according to Nourbese N. Flint, M.A.W.H., the senior director of Black leadership and engagement at Planned Parenthood Federation of America (PPFA).

These populations tend to bear the brunt of adverse health outcomes, often by a wide margin. Sexual violence is just one example, Flint shared. It disproportionately affects groups such as trans people, unhoused people, people with disabilities and people of color, according to Nelson.

"For every issue that the U.S. must address when it comes to sexual and reproductive healthcare, we must address an issue within. And that's equity," Fey said. "How do we build a country where people have reproductive autonomy regardless of who they are, where they live and how much money they make?

"The policies and resources I mentioned are good starts. But they all have one thing in common. They don't improve the whole unless they address the needs of those who face the greatest barriers."

As with improving the nation's sexual health, addressing health inequities will require a multifaceted approach involving actors at the individual, local, state and national levels, according to Flint and the CDC, which sponsors several evidence-based initiatives to this aim.

Likewise, Flint said improving outcomes for some can bring about benefits for all.

"Systemic inequities were created over a long period and will take time to undo. By centering the people who sit at multiple intersections and experience marginalization at multiple layers, we can address inequities from the ground up," Flint said.

She added that we know two things. First, everyone benefits if we solve inequities for the people who are most impacted. Second, no one-size-fits-all solution exists.

"We need multiple individuals, communities, industries and organizations working to address and undo inequities," Flint concluded.