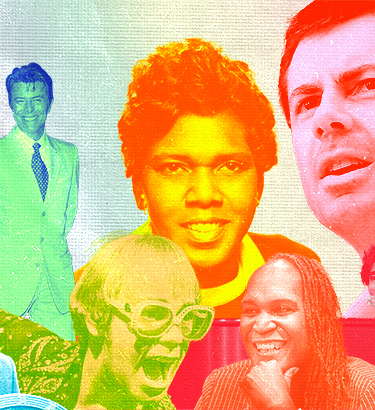

Welcome to a collection of Giddy articles on LGBTQIA+ history. Each week we’ll talk about a different part of the community’s past, present and possible future. This week, a look at how LGBTQIA+ public figures have changed over time.

"Hidden in plain sight" was the best deal available to a gay person in mid-20th century America. Whether your identity was an open secret or you could successfully pass as straight, having a career (let alone a career in the public eye) was no small feat for any queer person in those days.

So how did one decade transform America's attitude towards gay celebrities from a witch-hunt to one of covert curiosity? Harvard professor Michael Bronski credits pop culture, especially music, as the first conduit into broader acceptance.

"Sexuality becomes more permissible to talk about by the mid '60s—an object of fascination. Gender becomes more fluid," Bronski said. "The question of, 'Is David Bowie queer?' is a very good question because he's in drag on stage. Is Mick Jagger queer? He's on stage poncing around. Everybody knew Little Richard was queer. Few people really said it in public. Then it became more acceptable to say it."

Prevalent male musicians performing without regard to traditional ideas of masculinity introduced a new audience (mainstream straight culture) to notions of gender fluidity—it's difficult to hate someone when they're singing your favorite songs. In other words, it's easier to first have a queer star when they're earning other people plenty of money. However, when an equally queer person wants to represent their community, things get a lot harder.

"A lot of this has to do with the term 'respectability politics,'" Bronski continued. "Pete Buttigieg (former mayor of South Bend, Indiana and is currently U.S. Secretary of Transportation) is so respectable. He even has the boring 'wife' and now he has adorable children. When you look at it, if you're looking at show business, people's [expectations of respectability] level is low. If you're looking at authors, it's a little bit higher and if you're looking at public figures or at politicians even higher in terms of how respectable they have to be before they're able to actually come out."

By Bronski's understanding, there's a cultural food chain of what kind of public figures receive more leniency to deviate. Respectability politics, or how well one's public persona fits traditionally white Christian values—homeownership, marriage and a nuclear family, even idiosyncrasies and ways of presenting—is a type of assimilation. In order to break out of those standards, it's necessary to broaden representation in cultural inlets.

"Look at somebody like Barney Frank," Bronski said. "Coming out of Boston, a U.S. representative, it's pretty clear he's gay, but he finally comes out by the '80s as levels of acceptance rise in the culture. It was our right to have 'Will and Grace' on TV, our right to have bachelorette parties going to drag shows, all to have a politician who's going to come out."

Bronski links Frank's career to cultural shifts priming the nation for a more accepting society. These changes require countless factors, among them being breakthrough moments in public visibility.

"Leonard Matlovich, a decorated Air Force man, decided with the help of [gay rights activist] Frank Kameny that he was going to challenge it. And he did," said lesbian historian Lillian Faderman. "He said, yes, I'm a homosexual. I'm a decorated Air Force person. I want to continue to serve in the Air Force. He was on the cover of Time magazine, the first out gay person on the cover with his own face."

The revolutionary magazine cover presented America with an undisputed gay hero. Matlovich was incredibly vulnerable and brave to offer himself up to scrutiny, but there also had to be unseen cultural shifts for such a prominent magazine to even consider publishing such a proclamation. That said, its reasons for sharing his story didn't have to be entirely altruistic as the cover was shocking to most Americans, which meant an uptick in newsstand sales.

"[Harvey Milk] was not the first out politician, but he certainly got much more coverage than others," Faderman explained. "He wasn't [even] the first out gay person to run in San Francisco—Jose Saria had run in 1961. Harvey Milk announced in '73. Harvey got a lot of attention because, number one, he was a guy. It's always been true that the work women do is considered less important than what men do. Number two, he was very flamboyant. He just had a very 'out there' personality. And number three, of course, he was martyred and he became a huge icon for the gay community because of that."

Harvey Bernard Milk moved from New York City to the Castro District of San Francisco in 1972. Through somewhat theatrical campaigns, Milk was elected as one of the city supervisors. During his short time in office, Milk was instrumental in passing a bill banning discrimination in public accommodations, housing and employment on the basis of sexual orientation. Milk was assassinated on November 27, 1978.

"Not that he didn't do fantastic things in the 11 months he was in office—he did," Faderman added. "But I think he's remembered where Elaine Noble [the first openly homosexual candidate elected to state legislature] is forgotten, at least in part, because he was a martyr."

As Faderman points out, it's no coincidence the figures discussed above are almost entirely cisgender gay men. Oppression, whether in regards to race, sex, socioeconomic factors or more, can be present even within progressive movements. That's where the harmful elements of playing by a society's rules to change the society hurt individuals.

Not all gay heroes wear capes on stage. Some wear beige suits. The rise of openly queer politicians is an international phenomenon; even domestically, we have 11 members of the 117th Congress, two senators and nine representatives, who are out and proud.

While this is a massive victory composed of multiple ethnic groups, the majority of these politicians are cisgender white men and women. It seems that even as we make progress in who's considered acceptable to represent our communities, there's still much work to be done as the push and pull between fascination and conventional virtue continues.