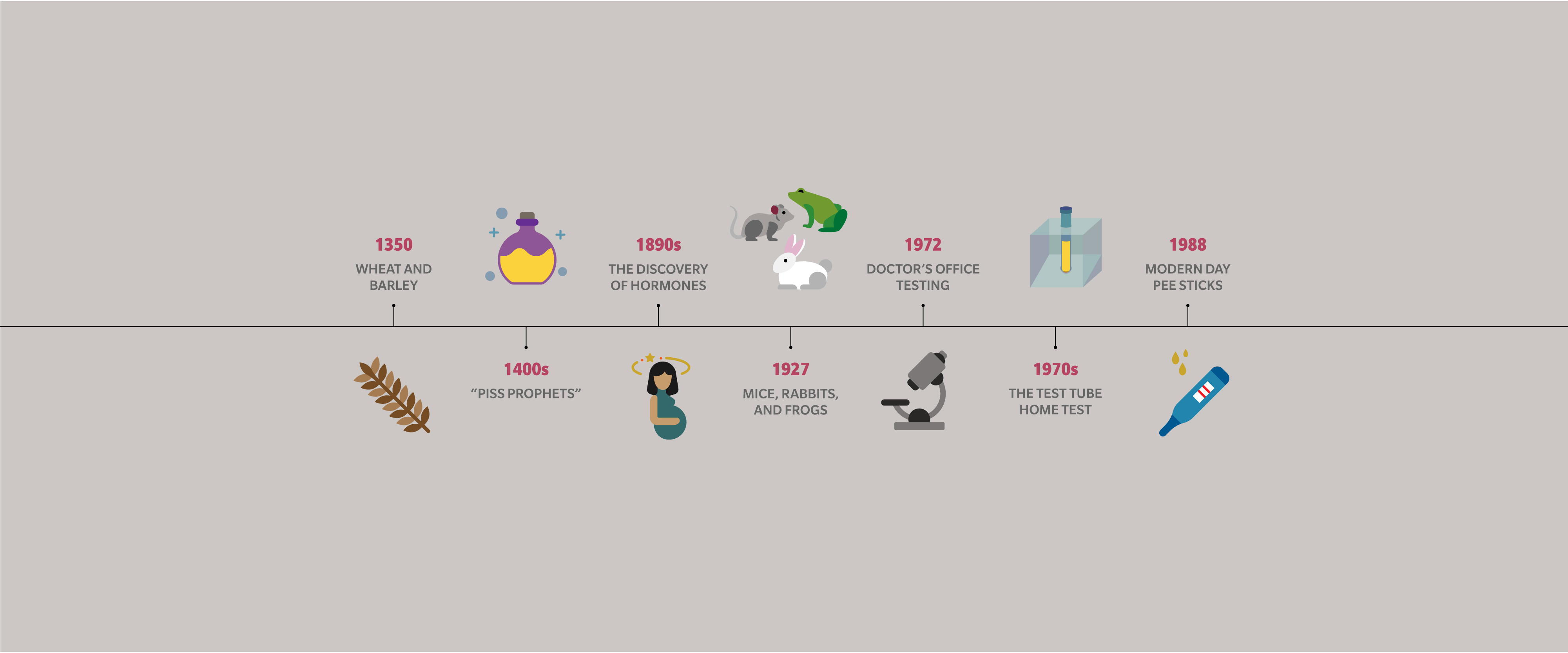

The earliest pregnancy test to be recorded was in use around 1350 BC, when Egyptian women were instructed to urinate on wheat and barley seeds. If the barley sprouted, they were likely pregnant with a boy; if the wheat sprouted, a girl. And if nothing sprouted, they weren't pregnant. (As outlandish as it sounds, one 1963 study found this method correctly predicted gender about 80 percent of the time.)

By the Middle Ages, women had transitioned from peeing on seeds to peeing in containers to be assessed by physicians, who looked for visible cues including granules, turbidity and color changes. These physicians specialized in the analysis of urine and were known as "piss prophets," who diagnosed a variety of medical conditions, including pregnancy. (Today, it's hypothesized that piss prophets were actually just attuned to a variety of more telling symptoms presented by the patient.)

In the 1890s, scientists became aware of hormones and started seriously studying how these chemicals impact and align with certain medical conditions. But they were still figuring out which hormones did what, and how to measure them. This would eventually prove pivotal. But at this time, women were still waiting for more obvious signs of pregnancy, like the continued absence of their period, morning sickness and weight gain.

It was also around this time doctors started encouraging women to make an appointment as soon as they suspected pregnancy. Even though there wasn't a reliable test yet, this focus on prenatal care had a positive impact on the health of infants.