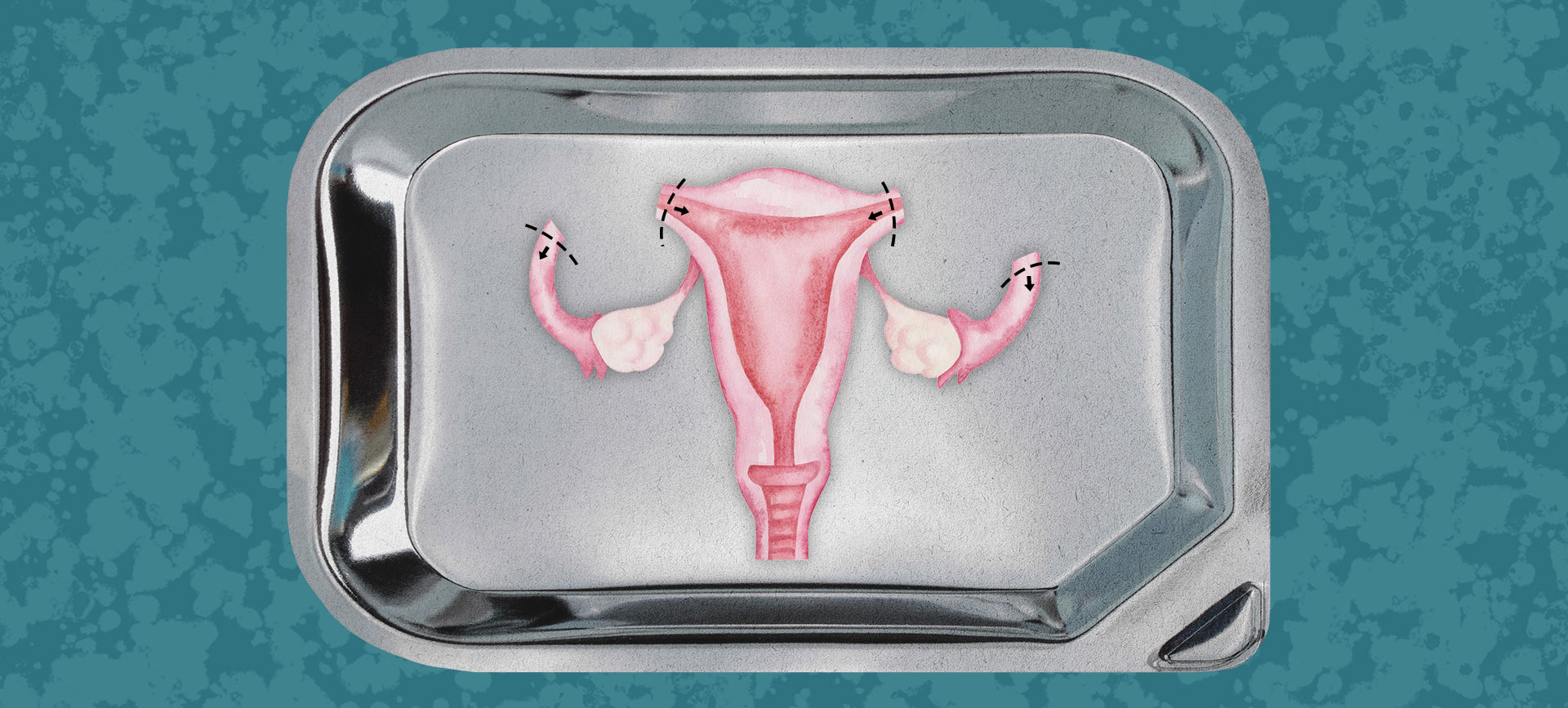

The procedure is called opportunistic salpingectomy (OS), and it involves removing the fallopian tubes during a hysterectomy procedure, which is the removal of the uterus.

"For several decades, there has been a hypothesis which has suggested that actually, ovarian serous cancer originates from the fallopian tube," said M. Bijoy Thomas, M.D., a gynecologic oncologist with the Lehigh Valley Health Network in Pennsylvania.

"So if fallopian tubes are removed preventatively, a woman is unlikely to get serous ovarian cancer," Thomas continued. "The recent JAMA publication looked at a large population of women who had a hysterectomy performed and found no serous carcinoma in women who had the fallopian tubes removed at the time of the hysterectomy."