Your State May Be Surveilling HIV Patients

The basic expectation for our personal and individualized health information to be safeguarded by the medical providers we entrust these parts of our personal lives to is probably a fair one. So when state agencies and governments take an active role in tracking, and possibly intervening with, the individual health choices we make, it creates a disconnect from our ideal and the reality.

Of course, considering public crises like COVID-19, we also understand active treatment and prevention of transmissible diseases is critical to our society at large. That said, the line between individual, autonomous rights and necessitated public health intervention is, in some ways, blurrier than ever.

If nothing else, this dichotomy highlights how patients need reliable communication from their healthcare providers. If a person is diagnosed with a transmissible illness regarded as a public health threat, it is important for said person to be fully educated and informed about the consequences of their diagnosis, symptoms, treatment and how they'll be treated by the state.

Unfortunately, people with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) often don't receive that last piece of crucial information.

Does HIV surveillance violate HIPAA?

If you've attended a doctor's visit since the late '90s, you may be familiar with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA). This federal law established the standards for protecting patients' health information from being delivered to third parties without the patient's consent, so doctors and medical institutions can't decide on their own to share your health information and decisions with other organizations or agencies.

If you've ever had medical records transferred from your primary care doctor to a surgeon or specialist, you might remember being presented with information about HIPAA and signing off on the transfer of records.

'I don't think it's done intentionally. [Patients] sign pieces of paper and they're not reading them carefully.'

A person's HIV diagnosis can be incredibly stressful and emotional. How a doctor pushes them to begin taking their medication immediately can be delicate or forceful, depending on the institutions and individuals involved, and there is generally a flurry of paperwork to review and sign. Given the cultural history of HIV and AIDS, newly diagnosed patients will likely be afraid for their lives and terrified of the social consequences of their diagnosis. In such instances, it is entirely unreasonable for someone in this situation to be expected to parse through dense documents of legalese and medical jargon in order to understand how they will be treated for the rest of their lives.

This is exactly what happens every day. Social workers and case managers with all manner of academic backgrounds may be available to the patient: The best of those will certainly take their time to explain legal documents and proceedings, which will eventually occur between doctor, patient and state. In less ideal circumstances, patients may receive little to no guidance in the avenue of informed consent.

"I don't think it's done intentionally," said Christine Brennan, a nurse practitioner and assistant professor at the Louisiana State University School of Public Health. "[Patients] sign pieces of paper and they're not reading them carefully. That happens all the time and it's very concerning to me. I see it all the time: Surgeons throw pieces of paper under people's noses [and say], 'here, sign,' and they don't know what they're signing."

The solution may be policy reform, or maybe a more generous distribution of resources.

"There are not enough caseworkers, there are not enough social workers. And, they don't get paid enough," Brennan explained.

The right to choose treatment

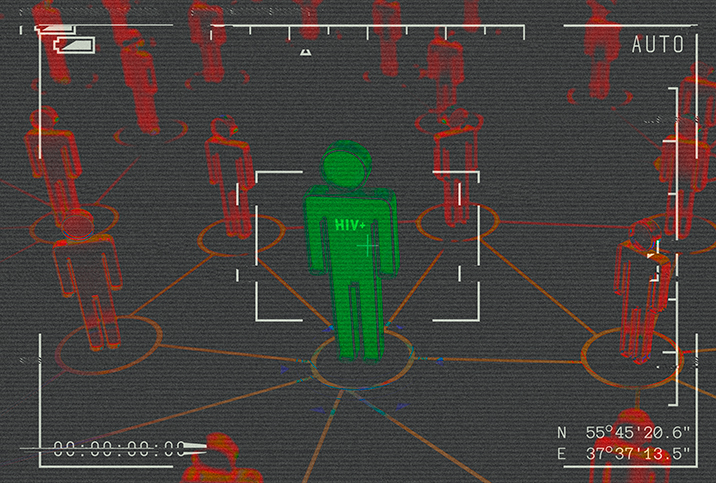

In Louisiana, which has one of the highest volumes of people living with HIV in the U.S., medical providers are required to share aggregated and individualized data with the state concerning HIV patients who refuse or fall out of treatment.

The purpose of this data sharing is to ensure HIV transmission is kept to a minimum and that patients who have fallen out of treatment—either by lack of opportunity or out of personal choice—are reengaged in treatment as soon as possible.

Most of the data reported to the state is confidential and conducive to statistical analysis of risk prevention and awareness. This data may include numbers of new diagnoses, percentage of on-treatment patients by age group or zip code, and data that may indicate areas of needed focus for education and engagement efforts. The aggregate data collected can vary based on location, the medical provider and/or resources available.

HIPAA enforcement is traditionally handled by the Department of Health and Human Services' Office for Civil Rights (OCR). State attorneys general have assisted enforcement and investigative procedures since about 2009, however. Several other federal agencies are known to coordinate efforts with OCR, as well.

"We see laws that disproportionately affect people living with HIV, right?" said MarkAlain Dery, D.O., MPH, FACOI, an infectious disease expert and HIV care provider with Access Health Louisiana serving the greater New Orleans area. He emphasized that even though Louisiana is predominantly white, HIV disproportionately affects non-white people and those in the minority of gender and sexuality spectrums. He pointed out statewide demographics are pretty much "flipped" when you look at the statistics surrounding people living with HIV/AIDS.

Even though Louisiana is predominantly white, HIV disproportionately affects non-white people and those in the minority of gender and sexuality spectrums.

Dery, who is also a co-founder of a radio station dedicated to human rights and social justice, had no problem identifying what all of this adds up to.

"So, really, these are the people for whom it's easy to discriminate against," he said. "It has become a political tool in our country. Politicians are not punished for doing so."

Holes in the patchwork

This issue is not indicative of an ethics lapse or inherent neglect on the part of doctors and medical providers.

HIV care providers are there to treat patients who would otherwise become severely ill or even face death. The fact that legislative powers and federal agencies choose to regard these individuals as public health risks despite scientific advancements, which all but rule out this perception as reality, should not be held against clinics, care centers or their staff.

Still, it's no secret that HIV and AIDS patients have long been the subject of politically and ideologically charged prejudice, and while it is inadvisable for a patient to go without HIV medicine, when someone chooses to do so, it should not be paramount to criminal behavior. What is unacceptable is neglect in areas such as patient education and consent.

There is frequently a gross disparity between the pay rates and education levels of those who have the most direct contact with HIV patients and those who have the least: Frequently, underpaid and overworked individuals bear the brunt of responsibility while receiving less-than-minimal support and training from the upper levels of staff hierarchy. This phenomenon has a direct and indirect impact on patient experience.

Healthcare workers deserve to be valued and appreciated, and that should be true at every level of community health service, not just the doctors, nurses, officers and directors of those institutions. And that in turn will pave the way for patients to be appreciated and treated as human, as well.